“I can never forget the excitement in my mind after seeing it. I have had several more opportunities to see the film since then and each time I feel more overwhelmed. It is the kind of cinema that flows with the serenity and nobility of a big river… People are born, live out their lives, and then accept their deaths. Without the least effort and without any sudden jerks, Ray paints his picture, but its effect on the audience is to stir up deep passions. How does he achieve this? There is nothing irrelevant or haphazard in his cinematographic technique. In that lies the secret of its excellence.”

Akira Kurosawa on Pather Panchali

The BBC had published a list in 2018 containing the artworks of celebrated directors around the world in several languages except in English. French films dominated the list occupying 27 places, followed by 12 Mandarin films, 11 Japanese films and 11 Italian films. The only Indian entry into the list is ‘Pather Panchali’ (Song of the Little Road) by Satyajit Ray which was released in 1955 and is placed at number 15 on the list. More than 200 critics from 43 countries were part of the selection process.

It all narrowed down to 100 films from 67 different directors, from 24 countries, and in 19 languages. Some of the notable films that featured in the list are — Kurosawa’s ‘Rashomon ‘, Wong Kar-wai’s ‘In the Mood for Love‘, Andrei Tarkovsky’s ‘The Mirror‘, Asghar Farhadi’s ‘A Separation‘, Guillermo del Toro’s ‘Pan’s Labyrinth‘, Ingmar Bergman’s ‘The Seventh Seal‘ and Alfonso Cuaron’s ‘Y Tu Mama Tambien‘, among others.

Christopher Nolan vowed to “watch more Indian films in future,” stating: “I have had the pleasure of watching Ray’s Pather Panchali recently, which I hadn’t seen before. I think it is one of the best films ever made. It is an extraordinary piece of work.”

So what makes it so unique? How did this iconic film change the direction of Indian Cinema and placed it on the global map? Let’s dig deep.

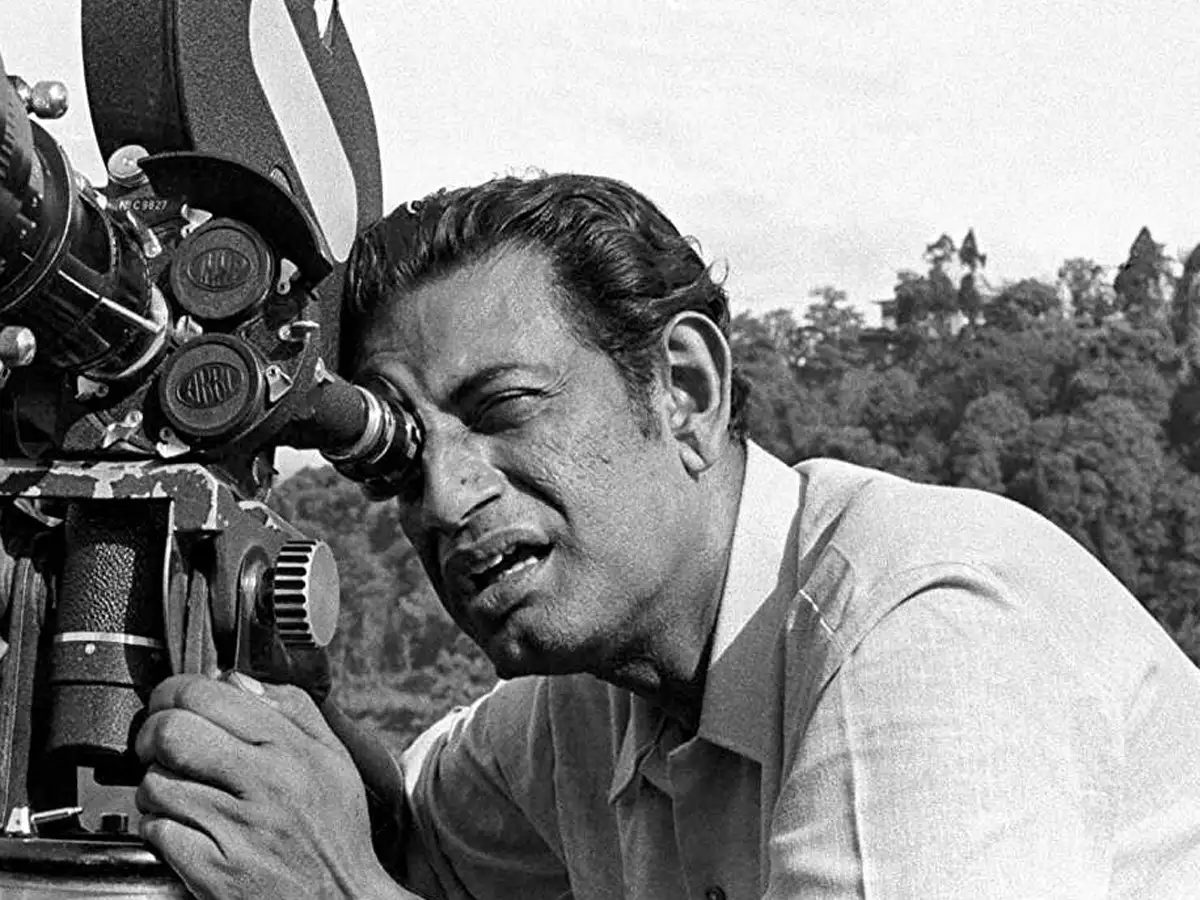

The Man Himself

Satyajit Ray, one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th Century began his ventures with this film. He was the grandson of the writer, illustrator, philosopher Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, and son of the pioneering poet, author, playwright Sukumar Ray. It was Sukumar Ray that gifted us with the evergreen “Abol Tabol”.

Though Ray completed his graduation in Economics, his interest was always in fine arts. In 1943, Ray started working as Junior Visualiser in a British advertising agency. Later he worked in a publishing house and created cover designs for books. He designed covers for many books, among which was children’s version of Pather Panchali, a classic Bengali novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, renamed as Aam Antir Bhepu. Designing the cover and illustrating the book, Ray was deeply influenced by the work. Thus, the seed of the greatest Indian film had been sown.

He later founded the Calcutta Film Society in 1947 where he screened many foreign films, many of which Ray watched and seriously studied. A couple of years later, French director jean Renoir came to Calcutta to shoot his film, The River. By this time, the idea of directing a making a film on Pather Panchali was already on his mind. He told his idea to Renoir, who encouraged him in the project. On his visit to London in 1950, he watched 99 films in three months. It was the neo-realistic approach of Bicycle Thieves by Vittorio De Sica in 1950 that influenced him immensely. Pather Panchali was the outcome of Ray’s enthrallment towards realism.

Ray went on to become one of the greatest filmmaker, screenwriter, music composer, graphic artist, lyricist and author. He was awarded the Honorary Academy Awards and the Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian award in India in 1992. And it all started with this film.

A Masterpiece in the Making

The film started, with Satyajit Ray, who had never directed a scene before; and his cameraman Subrata Mitra, who had never shot one. The film featured mostly new faces and operated by amateur crews. Perhaps this inexperience gave everyone involved the freedom to create something new.

The film was made on a shoestring budget. Ray had to sell his life insurance and pawn his wife’s jewellery to resume shooting. It was shot piecewise over three years; often, production was halted due to lack of funds. Eventually, the West Bengal Government provided enough money for Satyajit Ray to complete the film.

Boral, a village near Calcutta, was selected in early 1953 as the main location for principal photography, and night scenes were shot in-studio.

The soundtrack of the film was composed by the veteran sitar player Ravi Shankar, who also was at an early stage of his career, having debuted in 1939.

Apparently, Banerjee’s father was not to keen to allow his son to act in a film. But Ray told him, “Today, no one knows your son or me. But I’ll make a film that will change Bengali cinema. Then, all of Bengal will know both of us.” Now not only Bengal, but the whole world knows the artist and his masterpiece.

The film was released almost 64 years ago on August 26th in Basusree, a south Kolkata theatre that is still running. But before its theatrical release in Kolkata, Ray and his crew had submitted it to Museum of Modern Art’s Textiles and Ornamental Arts of India exhibition of May, 1955; and on 3rd May it was opened with a mixed response. Subsequently, the film had its domestic premiere at the annual meeting of the Advertising Club of Calcutta; the response there was not positive, and Ray felt “extremely discouraged”. The Basusree release also had received a poor initial response.

The film was screened at the Cannes Film Festival, 1956 on the then Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru’s personal recommendation. There were less than half a dozen people at the screening. One of them left barely 10 minutes after the lights were dimmed complaining loudly that he couldn’t stand its slow pace. That was Francois Truffaut. He had said, “I don’t want to see a movie of peasants eating with their hands”. Many dozed their way through the film. And if it wasn’t for the ones who were awake, especially the chief curator of the Cinematheque Francaise, Lotte Eisner; this masterpiece could have been lost in oblivion. Lotte persisted for another screening amidst protests as she could not believe her eyes. She was enthused by “Pather Panchali’s freshness and purity, the absence in it of any kind of stylistic or technical flamboyance”. And thus, the film went on to win the special jury prize for the “Best Human Document”, which, in turn, persuaded Ray to chuck up a career in advertising and devote all his time and energy to films.

Unreeling the Plot

The time is early twentieth century, a remote village in Bengal, Nischindipur. The film deals with a Brahmin family, a priest – Harihar, his wife Sarbajaya, daughter Durga, and his aged cousin Indir Thakrun – struggling to make both ends meet. Harihar is frequently away from home on work. The wife is raising her mischievous daughter Durga and caring for elderly cousin Indir Thakrun, whose independent spirit sometimes irritates her. Apu is born. With the little boy’s arrival, happiness, play and exploration uplift the children’s daily life.

Durga and Apu share an intimate bond. They follow a candy seller whose wares they cannot afford, enjoy the theatre, discover a train and witness a marriage ceremony. They even face the death of their aunt – Indir Thakrun.

She falls ill after a joyous dance in rains of the monsoon. On a stormy day, when Harihar is away on work, Durga is taken ill and passes away.

On Harihar’s return, the family leaves their village in search of a new life in Benaras. The film closes with an image of Harihar, wife and son – Apu, slowly moving away in an ox cart, through a ‘little road’.

Ray wrote that he had omitted many of the novel’s characters and that he had rearranged some of its sequences to make the narrative better as cinema. Changes include Indir’s death, which occurs early in the novel at a village shrine in the presence of adults, while in the film Apu and Durga find her corpse in the open. The scene of Apu and Durga running to catch a glimpse of the train is not in the novel, in which neither child sees the train, although they try. Durga’s fatal fever is attributed to a monsoon downpour in the film but is unexplained in the novel. The ending of the film—the family’s departure from the village—is not the end of the novel.

Art of Narration

Humane treatment of characters, natural acting, attention to details and the sensual usage of nature as a backdrop were what made the film unique. Ray was one of the pioneers in the parallel film movement in India along with Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak. Pather Panchali was the commencement of that genre.

Consider the scene of realization of Durga’s death by Harihar. This happens when Harihar returns to find his house ruined and his daughter dead, followed by Sarbajaya’s breakdown. Her grief-stricken cry is expressed by her own voice by the Esraj playing a passage of high notes. This not only intensifies the mother’s pain but also moulds it to be universal.

A personal favourite sequence of mine is the passing away of Indir Thakrun. Her solitary death, followed by the children discovering the corpse, was entirely Ray’s invention; as Durga playfully shakes her squatting form, it crashes over and her head hits the ground with a sickening thud. Though Chunibala Debi (the actress) initially was reluctant to act this scene, Ray persuaded her to do it and Ray says in an interview that there was a mixture of elation and exhaustion after she did that scene.

Orchestra of Natural Beauty

Like a definitive artist, Ray had worked on the minute details, planning and improvising on them to capture subtle moments if nature. Before the commercial production, many scenes were even sketched by Ray himself.

The water-skaters and dragonflies floating and exploring the plants in the pond, which resembles Apu exploring the village; the larger-than-life witch-like shadow falling on the wall from the lamp at night during the time of storytelling; and the memorable and majestic train scene with the black smoke in the backdrop of white Kaash flower fields – these scenes speak volumes of what a brilliant filmmaker Ray was.

An iconic scene (and yet another favourite of mine) lies at the end of the movie when a snake crawls into the deserted house after the family’s departure from Nishchindipur. It’s interpreted by many as the “Baastu-shaap” (a snake who lives in old, often abandoned homes guarding valuable property).

Through the Looking Glass

The technical team included several first-timers, including Ray himself and cinematographer Subrata Mitra, who had never operated a film camera. Art director Bansi Chandragupta had professional experience, having worked with Jean Renoir on The River. Both Mitra and Chandragupta went on to establish themselves as respected professionals.

Mitra had met Ray on the set of The River, where Mitra was allowed to observe the production, take photographs and make notes about lighting for personal reference. Having become friends, Mitra kept Ray informed about the production and showed his photographs. Ray was impressed enough by them to promise him an assistant’s position on Pather Panchali, and when production neared, invited him to shoot the film. As the 21-year-old Mitra had no prior filmmaking experience, the choice was met with scepticism by those who knew of the production. Mitra himself later speculated that Ray was nervous about working with an established crew.

The film depicts that Ray’s camera is always where it needs to be. He and Mitra both had an extraordinary capability to look into the same thing differently from others and that helped them much in shooting their very first film.

Melody of Human Emotions

Ravi Shankar composed the most important passages of music in an all-night session lasting eleven hours until 4 am in the morning, because of his busy schedule. He already knew the novel of Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyaya, on which the film is based, when Ray met him. He hummed a melody with the feeling of a folk-tune about it that became the main theme of the film, usually heard on a bamboo flute.

Shankar also composed two solo pieces – a spiritually uplifting one in Raga Desh which is conventionally associated with the rains and a somber piece Raga Todi to follow Durga’s death in the storm. The high notes of Esraj played when Sarbajaya bursts out in grief were played by Daksinranjan Tagore in Raga Patdeep, chosen by Ravi Shankar. The film’s cinematographer, Subrata Mitra, performed on the sitar for parts of the soundtrack.

The soundtrack is featured in The Guardian’s 2007 list of 50 greatest film soundtracks. It has also been cited as an influence on The Beatles, specifically George Harrison.

A Visual Poetry

“There is something very universal about this film that is never bogged down by details and this struck me deeply. There is so much Bengal in the film and yet it is so universal.”

– Aparna Sen, screenwiter, filmmaker, actress and one of Ray’s leading reel women

Ray, being one of the country’s biggest and most renowned cinephiles, has evidently seen and absorbed a large cross-section of world cinema that spans various decades, geographies and cultures. And Pather Panchali stands as a testament for that wherein Ray incorporates many of his influences without ever making it look contrived or out of place. Apart from the overt nods to the neo-realist customs, Ray constructs sequences that conform to Eisenstein’s rules of montage, the scene where Durga is punished by her mother stands out, employs indoor sets that have an expressionistic touch to them. Some of his compositional practices, too, show closeness to Japanese cinema.

Pather Panchali is the first film of ‘The Apu trilogy‘. The remaining two films of the trilogy, Aparajito and Apur Sansar, follow Apu as the son, the man and finally the father. Though the film deals with the grim struggle for survival by a poor family, it has no trace of melodrama. It’s a universal humanist appeal that is projected instead.

Pather Panchali opened the eyes of the world to the beauty that lay in the most unexpected of places – rural, poverty-striken Bengal. It’s the unconventional artistic narrative, thr graceful portrayal of the struggling lives, a perfect casting, the moments of beauty and joy caught in ordinary life, and its visual integrity that makes this film so transcendent, and such a delight even on repeated viewing.

“Money makes the world go round” – Javier Peña, DEA

“If series are good to watch then no body will by the books” – D&D inspired by R.R.Martin

LikeLiked by 1 person

A beautiful and haunting film. I’ve seen it only once, several years ago, but have never forgotten it. It truly is one of great films.

I’m kind of shocked at Francois Truffault’s reaction. But maybe he watched it again later and changed his mind…?

Thank you for sharing your research and thoughtful analysis. You’ve persuaded me to see this again very soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for liking my analysis, and please watch all of Ray’s work since he, along with his contemporaries Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak had changed the landscape of Indian cinema on the global scale.

Yes, Truffaut later retracted his remark and apologized. He even considered “Pather Panchali” an example of a primitive and exotic national cinema.

LikeLiked by 1 person