An 18-year old IIT aspirant allegedly committed suicide in her hostel room in Kota, just a week ago. In December 2018 three suicides under the span of 48 hours shook the nation. This alarming rate of suicides is what brought down Kota, the coaching capital of India to a “suicide city”. Be it the insane stress of competition, complete isolation from home and outside world, pressure from parents and peers, jealousy and loss of self-confidence – it’s the lack of solutions to these which lead students to a nervous breakdown and press the Quit button.

Created by Saurabh Khanna (Yeh Meri Family), with a lesser known team of directors Raghav Subbu, DoP Jerin Paul and writers Abhishek Yadav and Himanshu Chauhan, Kota Factory is a perfect representation of the present education system in India, especially the struggle in the daily life of an IIT-aspirant. This tragi-comedy series from TVF (The Viral Fever) addresses most of the problems a student might face in a place like Kota. Moreover, it focusses on solutions rather than the problems, thus being a breath of fresh air in this gloomy setting.

“Hum to yahan tab se hain, jab yeh Kota factory nahi sheher hua karta tha” – this line said by an autorickshaw driver just after a few minutes into the first episode illustrates how this city has transformed since 1985 when the first student of V.K. Bansal cleared the IIT-JEE examination, to the present where the city churns out an assembly line of toppers.

The five-episode series follows the story of Vaibhav Pandey (Mayur More), a wide-eyed IIT aspirant from a small town with big dreams. He fails to get in the best coaching institute Maheshwari (despite having scored 90% in 10th standard), and his father has no other option left but to get him a seat in a rather less prestigious institute Prodigy.

More than answering the crucial question of whether Vaibhav will crack the IIT-JEE, the show excels in portraying the personal and educational challenges he faces and how he overcomes them in the course of one year. It is during this journey of his that we understand the importance of good friends and teachers.

The performances complement the setting. Ranjan Raj steals the scene with his portrayal of geeky Meena. His meek and frequent jump to class-consciousness is a friend we all wish we had in our lives. When he asks, “Tum ameer log kabhi bhi cake kha lete ho?”, you can’t help but adore his child-like innocence. His character is balanced by the funky Uday (Alam Khan). The two represent the narrative extremes of Kota – Meena, the hard-working “quota” admission determined to justify his place, and Uday the chiller, wasting away his boyhood. Alam Khan has played a similar character in the past – Chudail in Laakhon Mein Ek.

Ahsaas Channa, as the bossy girlfriend Shivangi Ranawat, has small but significant appearances in the show. Her character is a commentary on women in Kota – outnumbered but thriving in the testosterone filled city.

Jitendra Singh’s Jeetu Bhaiya is our only hope for redemption in the city. He is the self-proclaimed “agony aunt” who solves any problem that the students face – academic as well as personal. He is the one that takes away the gloom and replaces it with practical solutions. Such natural acting deserves some praise. This mentor and guide not only shocks our newbie Vaibhav about the truth about the educational system but also opens his eyes. He is the only ray of hope when everything around you seems like adding to the darkness.

“Bacche do saal mein Kota se nikal jaate hai. Kota saalon tak bacchon se nahi nikalta (Students leave Kota in two years, but the place doesn’t leave them for years).”

Jeetu Bhaiya, the star teacher gives us an idea about not only how the city contributes to making the students who they are, but how hellish this same place can be

The biggest asset of the show is its writing by Abhishek Yadav, Saurabh Khanna and Sandeep Jain and the direction by Raghav Subbu. The fourth episode distracts from the trajectory of our protagonists, but there are moments that develop the characters and how they express the most cinematic emotions solely through the language of academics. This is shown through all the study dates of Vaibhav with Varthika, and her reciprocating love by asking the hesitant, shy Vaibhav whether they shall start the 12th syllabus from the very next day. Also, their unspoken bond is denoted by the pre-exam “dahi-shakkar” scene.

Inorganic Chemistry is an obvious target of a 3-minute rant by Vaibhav and shows his hatred towards the subject. One of the most important lines is in the finale when Meena says “Friendship is not revision; that you have to do” while parting with his best friend.

The original songs with the apt background score go perfectly with the monotone but also pumps energy into the bursts of emotions that our characters feel.

The only flaw that the show suffers is the overt placement of sponsors. Its sponsored by Unacademy, an online educational platform. Though the product integration is not as jarring as in TVF’s Tripling, after a point it starts taking away from the main story and starts becoming a distraction.

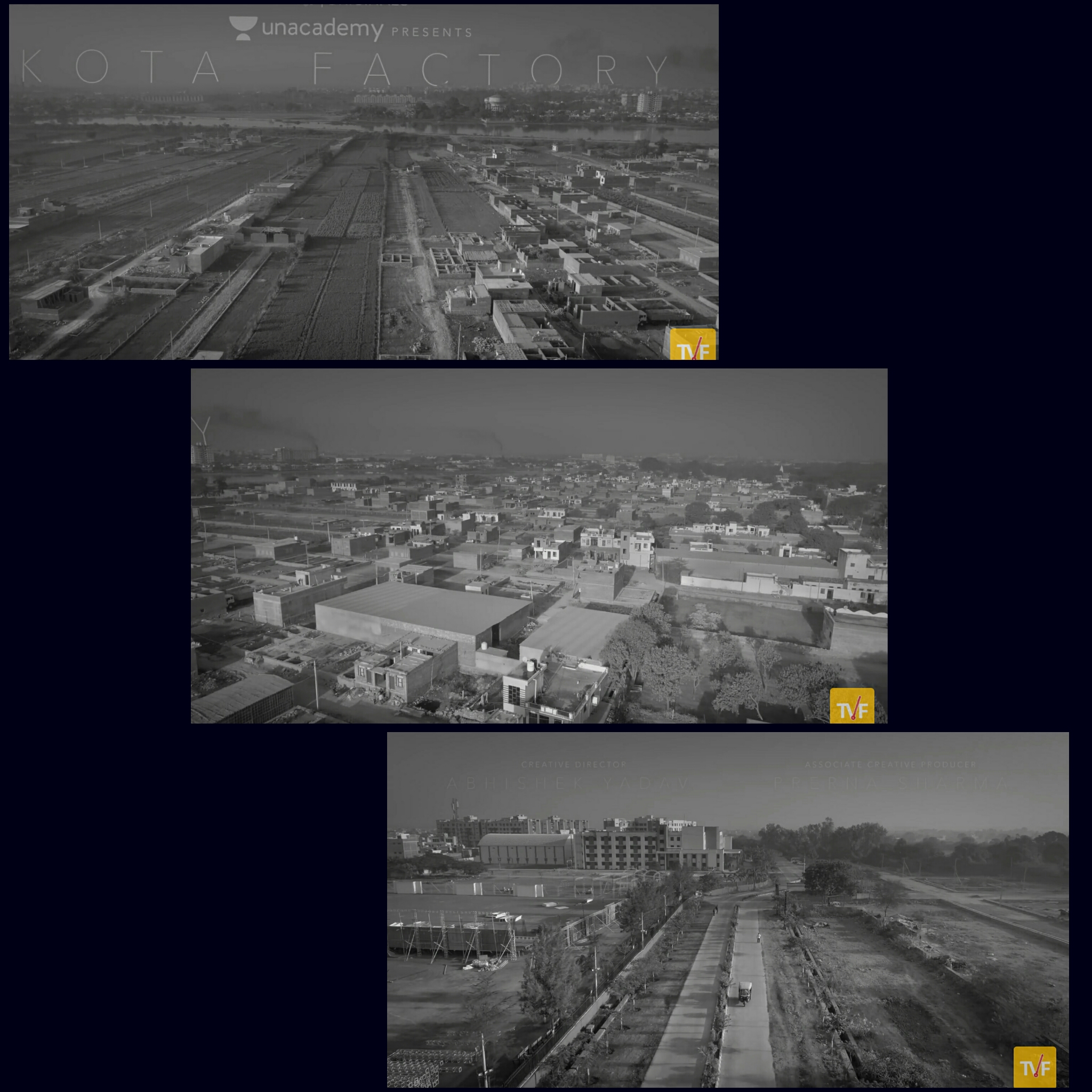

The signature top-angle drone shots present Kota’s circuit-like topography and reflect our lead character as just another hamster in this huge maze. The first episode ends with a striking shot – the camera moves up high to show Vaibhav, upgraded to batch A5 from A10, gradually adapting to the surroundings. It zooms out further through an opening in the roof as if we are observing the kids through a keyhole of a prison chamber.

After a long time, we have an educational satire playing on a new genre and story-telling with strong performances. Rather than making you think about death, darkness and gloom the show leaves you with a note of optimism. All of this makes Kota Factory a very genuine show – perhaps the best since TVF’s Pitchers. So go and binge-watch it on YouTube (Yes it’s free!).

To end with, I want to talk about the ingenuity of the makers for taking this show one step further – releasing it in Black and White. I’m sure there must have been a long discussion whether to do this and plenty reasons not to. But how right they were!

The show starts in colour. Then, it turns monochrome as the protagonist comes into the frame. This is an allusion to the fact that we are entering the world of Kota through his eyes. The monochrome cinematography replicates the gloomy setting of the city, and takes us on the roller-coaster ride of Vaibhav, as he sets on his journey. It shows us the real truth under the rose-painted walls of the city, and also delves us deep into the emotions of the people residing in it.

If you look closely, the show changes back to colour in the very last scene, where the more confident Vaibhav now knows how to cope with problems, and in turn, goes on to impart the solution given by Jeetu Bhaiya to a fellow new entrant in this rat-race. Thus the story pans through one year; how the next door Mumma’s boy who was even struggling with canteen food, is now matured enough to be ready to take any new challenges.

This monochrome masterstroke resonates the famous saying by the Trotskyist Ted Grant, “When you photograph people in colour, you photograph their clothes. But when you photograph people in Black and White, you photograph their souls!”