“Anime may depict fictional worlds, but I nonetheless believe that at its core it must have a certain realism. Even if the world depicted is a lie, the trick is to make it seem as real as possible. Stated another way, the animator must fabricate a lie that seems so real viewers will think the world depicted might possibly exist.”

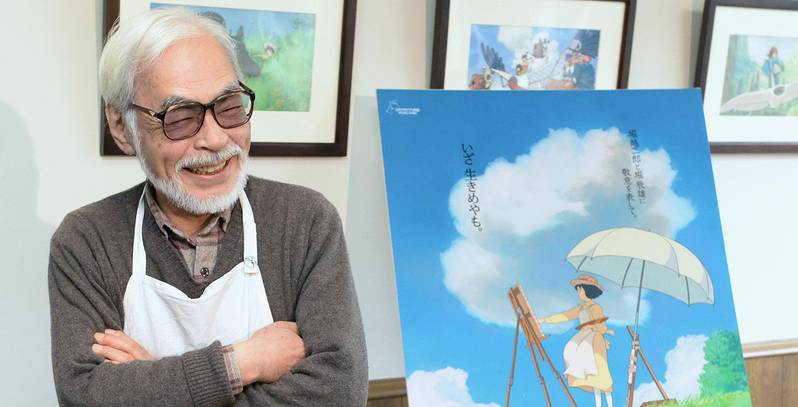

– Hayao Miyazaki

Over the last three decades, Miyazaki, and his company Studio Ghibli, have been behind some of the greatest masterpieces that animated films have ever seen, strange wonderful pictures that couldn’t have come from anywhere or anyone else, and have broken out of love from just the hardcore anime fans to enchant audiences and cinephiles the world over.

After writing and directing the 1997 animated epic Princess Mononoke, Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki announced that he was planning to retire. And thankfully he changed his mind.

Not often does a film truly transport viewers outside themselves–or deep inside. One such precious vehicle is Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, which has shown its class and mass appeal by winning the top prize at 2002’s Berlin Film Festival (being the first animated film to do so) and also winning the Best Animated Feature Film at 2003’s Academy Award.

The movie is called Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (千と千尋の神隠し). Kamikakushi means spirited away with kami meaning spirit or god and kakushi meaning hidden. So perhaps we can translate the title as “Sen and the Mysterious Disappearance of Chihiro.”

Spirited Away was released in Japan in July 2001. Most Studio Ghibli movies were released in July, and in Japan, I feel this is especially significant in the case of Spirited Away and also When Marnie Was There because it is the Obon season, a time when Japanese believe the spirits of their ancestors walk the earth and return to their furusato (hometown). It was a blockbuster in Japan, where it out-grossed the previous chart-topper Titanic.

Western audiences have caught on the enchantment of anime thanks to the patronage of Disney and Pixar chief John Lasseter, perhaps the only figure who can stand alongside Miyazaki in the animated world. Disney executives, knowing a good animated film, bought the worldwide rights to Spirited Away and refitted it with an English script and a new voice cast that includes such American actors as Suzanne Pleshette, David Ogden Stiers and Daveigh Chase, last heard as Lilo in Disney’s Lilo & Stitch.

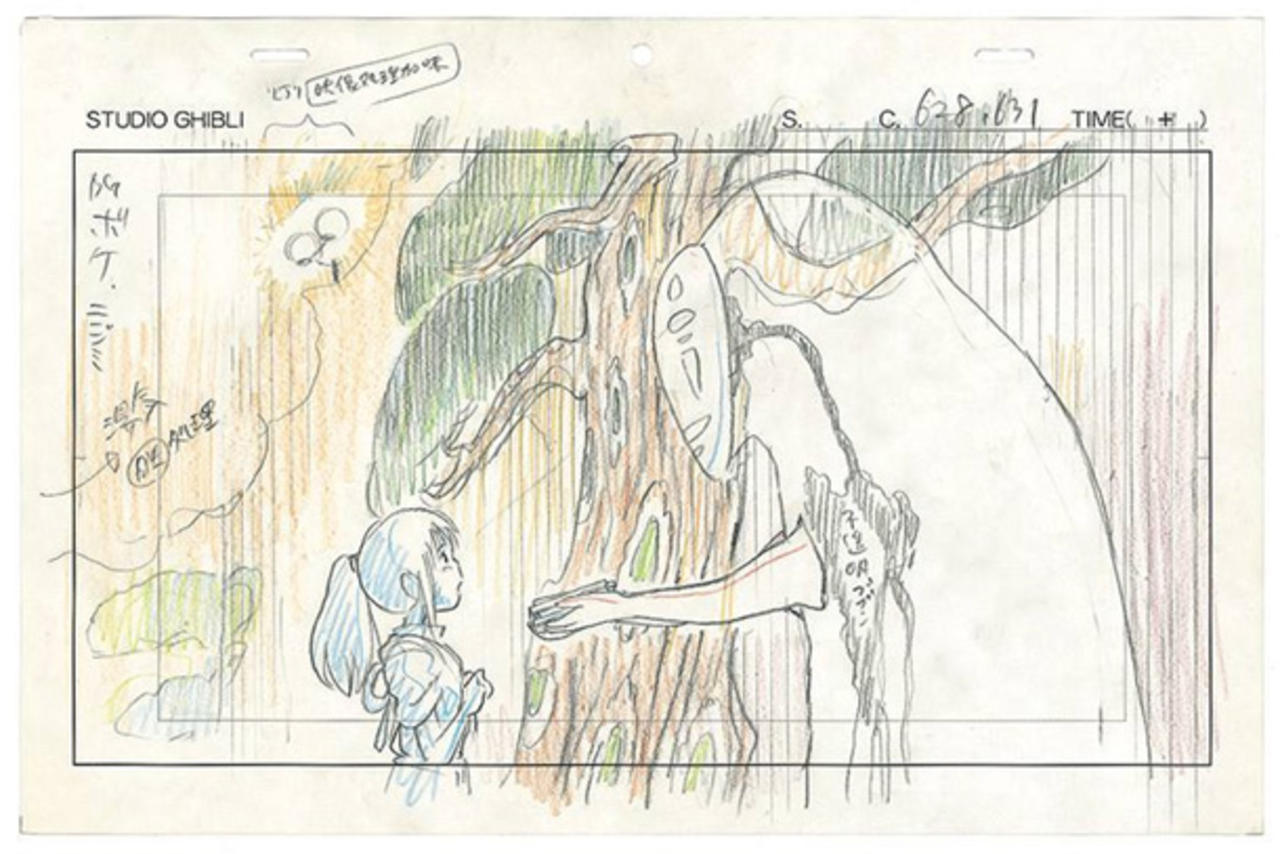

The result is nothing less than magical, which in turn is a throwback to the very best of early Disney. Spirited Away, which is mostly (and gorgeously) hand-drawn but has computer-generated assists throughout, tells the story of Chihiro (Chase), a 10-year-old who follows her impulsively curious parents into a seemingly abandoned theme park, where the adults gulp down food at an empty midway kiosk and turn into snorting pigs. Alone and frightened, Chihiro is taken under the wing of Haku (Jason Marsden), a mysterious boy with magical powers who explains that she’s in a land where humans are not allowed, then advises her on the first step of her great escape.

Gradually, in a series of almost episodic adventures, she learns to be brave and face up to her responsibilities to herself and the people she loves. The baseline material is fairly standard stuff for a child’s adventure story, but the complex trappings and the shape of that story are uniquely Miyazaki.

As in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, each character seems like an entire, endlessly suggestive world in itself. If Yubaba is the scariest of the characters and Kamaji the most intriguing, Okutaresama is the one with the most urgent message. He is the spirit of the river, and his body has absorbed the junk, waste, and sludge that has been thrown into it over the years.

Even the bathhouse is a character in itself. It feels alive and real. While it’s inherently unbelievable, we believe it exists in the context of the world of Spirited Away because it’s so well established: there are employees with jobs to do, sleeping quarters, a coal-powered furnace that heats the baths, different kinds of soap for different clients, even a process by which to call certain kinds of soap for different kinds of baths.

The parallels to “The Wizard of Oz” are pronounced too, but Chihiro’s adventures may have more resonance for contemporary kids. It’s all a metaphor for her dread of a new neighborhood and a new school, and in proving to herself that she has the courage, ingenuity, and determination to get the job done in her fantasyland, she overcomes her fears back in the real world.

Japanese animation doesn’t attempt to match the fluid motion of Disney’s best hand-drawn features, and the characters have none of the fine motor skills of an Aladdin or a Simba. But Miyazaki’s animation is, in its detail, as rich or richer, and his imagination is something, literally, to behold. Miyazaki uses ancient Japanese superstitions about ubiquitous spirits as his inspiration, and some of the spirits are ghosts behind kabuki masks. But this version of Spirited Away has no cultural speed bumps for anyone, and its themes about love and self-esteem are universal. At just over two hours, Spirited Away is an epic among children’s animated movies, but it flies by, thanks to both Miyazaki’s endless inventiveness and his unerring feel for his heroine.

Unfortunately, this award also followed Miyazaki’s official announcement of retirement, making The Wind Rises his final feature film with Studio Ghibli.

Miyazaki’s stories can go in two directions, that of complexity or simplicity. In his more complex films (Princess Mononoke, Howl’s Moving Castle), the plot can escalate to dizzyingly metaphysical levels, and his indulgence in the bizarre can occasionally mystify his audiences. Critics didn’t know how to respond to Howl’s, as the final half-hour goes into mind-boggling explorations of character history through the medium of a magical door in the wall. This complexity that can be found in his more adult films is represented symbolically by a recurring theme of things falling apart. You may not understand what is going on but you know you want to keep watching.

The other side of the coin is in the joyous simplicity that can be found in My Neighbour Totoro, Ponyo, and, to a lesser extent, Porco Rosso and Kiki’s Delivery Service. It takes someone truly special to create a film entirely devoid of conflict and still manage to make it engaging. Miyazaki, with Totoro, does this and more. The beauty of these movies lies in their simplicity.

Spirited Away sits on the edge of that coin, having the probability to fall on either side. Dream and nightmare, the grotesque and the beautiful, the terrifying and the enchanting all come together to underline the oneness of things, to point out how little distance there is between these seemingly disparate states, much less than we might imagine. Miyazaki no doubt intended the opposition of these images to have an effect on us.

Miyazaki’s luminescent, gorgeously realized world is relatively safe for children (good defeats evil and love conquers all, though it’s more important that honesty, courage, and personal integrity are always eventually rewarded), but it also acknowledges blood, pain, dread, and death in ways that other animated films wouldn’t dare. Spirited Away is nowhere near as grim and despairing as Princess Mononoke, but neither does it take place in the effervescent, sunny worlds of Miyazaki classics like My Neighbor Totoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service, where there are no bad guys, only bad moments. It occupies a more adult place, where life lessons are frightening and hard-won. But it implies—with passion, humor, heartbreakingly lovely animation, and no preaching.

Let’s think about the word animate — “to bring to life.” This is acting. Miyazaki argues that animators are themselves actors; they must understand and empathize with their characters.

In the review of The Lion King (2019), I had written that in animated films, voice acting and animation – both should be aligned together. Voice acting is disembodied until it’s attached to a drawn character. A character’s unspoken mannerisms and facial expressions are equally important in establishing a character as what they say.

To get a better sense, let’s look at running. To convey the illusion of running, animators use a run cycle — an animated sequence that depicts running strides. Over time, animators have developed a reliable, standardized approach to the run cycle — a sequence of four steps per second, six frames per stride. This is just a guideline and of course, there are many different ways of running, and every character runs a little bit differently, depending on the circumstances and their reason for running.

It takes finesse to construct a truly believable and compelling run cycle, one that is appropriate to the character, their emotion, and their intention. It’s incredibly precise — an extra frame here or there can destroy the rhythm and lead to a stilted, awkward-looking sequence. Whenever you see a character running in a Ghibli film, the animator has considered the character’s motivation for running and imparted that motivation into the way the character moves.

Achieving realistic movement is really difficult to accomplish that many filmmakers have used the technique of tracing live-action footage as an easier shortcut to accomplish a realistic result, a process known as rotoscoping. Though I’m not taking anything away from rotoscoping, which has now become a creative animation and VFX technique in its own right, and need skilled artists to ensure that everything is in the right place at the right time; there are subtleties to a character’s behaviour which are lost or don’t translate properly through this technique. It was never animation’s task to emulate real life. It’s to create an analog, so to speak; some imaginary world adjacent to and reminiscent of our own, but not necessarily identical.

“I think 2-D animation disappeared from Disney because they made so many uninteresting films. They became very conservative in the way they created them. It’s too bad. I thought 2-D and 3-D could coexist happily.”

– Hayao Miyazaki, when asked about the vanishing art of 2-D animation from the Disney films

Animators can take the rules of our world and bend or break them however they wish. That’s part of the magic of animation, and this “plausible impossible” is what made the great Walt Disney interested in animation. But to achieve a level of immersive realism, there must exist an underlying familiarity with the characters and the world where the story takes place. That familiarity comes from the details. Hayao Miyazaki is famous for the throwaway details at the edges of the screen, which are like punctuations in a very well-written novel. We could very well have it with just a few of them, but it’s these details that make his creations so flawless and enrapturing. And accompanying the visuals is a very beautiful score by Joe Hisaishi. The music ranges from soft, warm and welcoming to dark and intense and one can’t get enough of it.

The world of Spirited Away is strange, but at the same time, one can’t help but look at it and feel a welcoming tone. As if Miyazaki wants you to feel welcome to this world he’s created. There are many moments in the story where dialogue will take a backseat and the animation and atmosphere will tell the story. These moments in particular really show off some striking visuals without sacrificing the pacing or storytelling as a result. This is one film that will make you appreciate animation as an art form and the magical power this artform possesses to spirit you away from reality.