“We Indians do not celebrate our genius, that’s why we need a Richard Attenborough to present our Gandhi to the world. And, we do not appreciate technology as an art, that’s why Subrata Mitra’s retrospective is celebrated in Italy, not here”

Ashok Mehta, National award-winning cinematographer of films like Bandit Queen, Moksha and 36 Chowringhee Lane

Cinema, as we are told, is a director’s medium just as the theatre is the actor’s. Both of the observations, to say the least, are erroneous. The cinematographer – the cameraman, of old – was and still continues to be the one who captures the director’s vision on film and creates the ground for its interpretation. It is he who gives the viewer a glimpse into the director’s mind and soul.

It would not be wrong to suggest that Satyajit Ray’s prodigious growth as a filmmaker was in direct proportion to Subrata Mitra’s as a cinematographer.

Subrata who? Precisely.

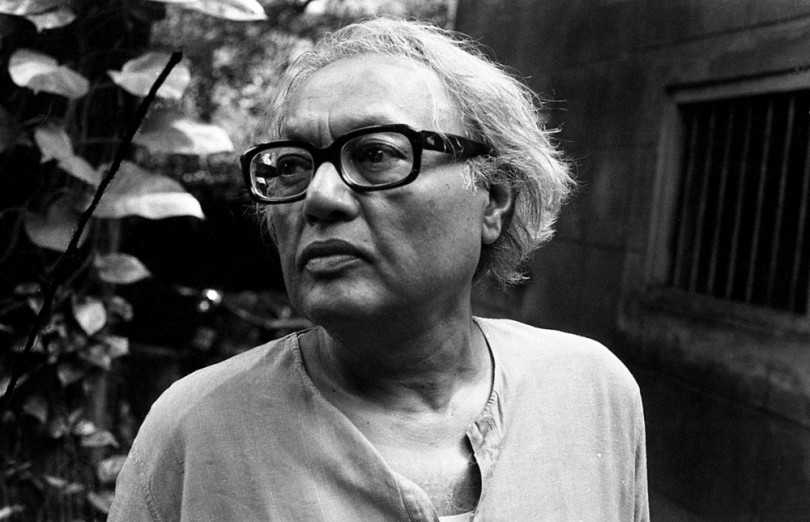

On his 18th death anniversary, let us try to give this genius of a man, a tribute that he had truly deserved, but never received.

The Confluence of Two Masters

Subrata Mitra was born into a middle-class Bengali family on October 12, 1930. Even as a schoolchild, he would cycle with classmates to the nearest cinema to watch the British and Hollywood films. By the time he was in college, he had decided he would either become an architect or a cinematographer. Failing to find work as a camera assistant, he reluctantly continued studying for his science degree.

In 1950, the great Jean Renoir came to Calcutta to shoot The River. Mitra tried to get a job on the film but was turned away.

Stubborn as he was, he didn’t take no for an answer, hung around and followed the unit with his little notebook in which he wrote and made meticulous sketches detailing the lighting, movement of camera and actors. This paid off, for later the cameraman Claude Renoir was asking Subrata for his notes on the film to check on his own lighting schemes.

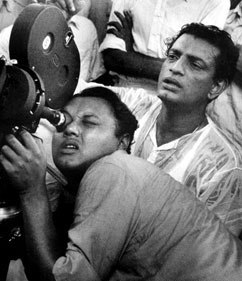

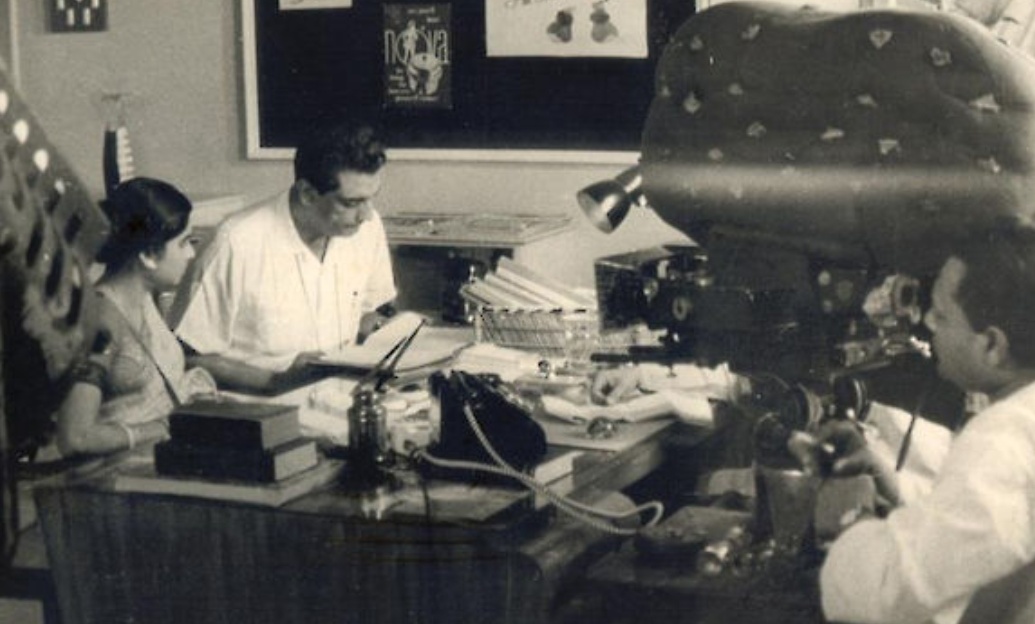

Also visiting the sets on Sundays and holidays to watch the shooting was a graphic designer and a friend of the art director. Mitra became friends with him and would visit him every day and describe in great detail what he had witnessed at the shooting. The other gentleman was planning to make a film and one fine day he asked Mitra to photograph the film for him. And so at the age of 21, Mitra became a director of photography.

The film he was to photograph?– Pather Panchali, and the director? – Satyajit Ray of course.

This is how, two highly gifted technicians, who turned their technical skills into a fine art without any formal training, found themselves at a strange confluence.

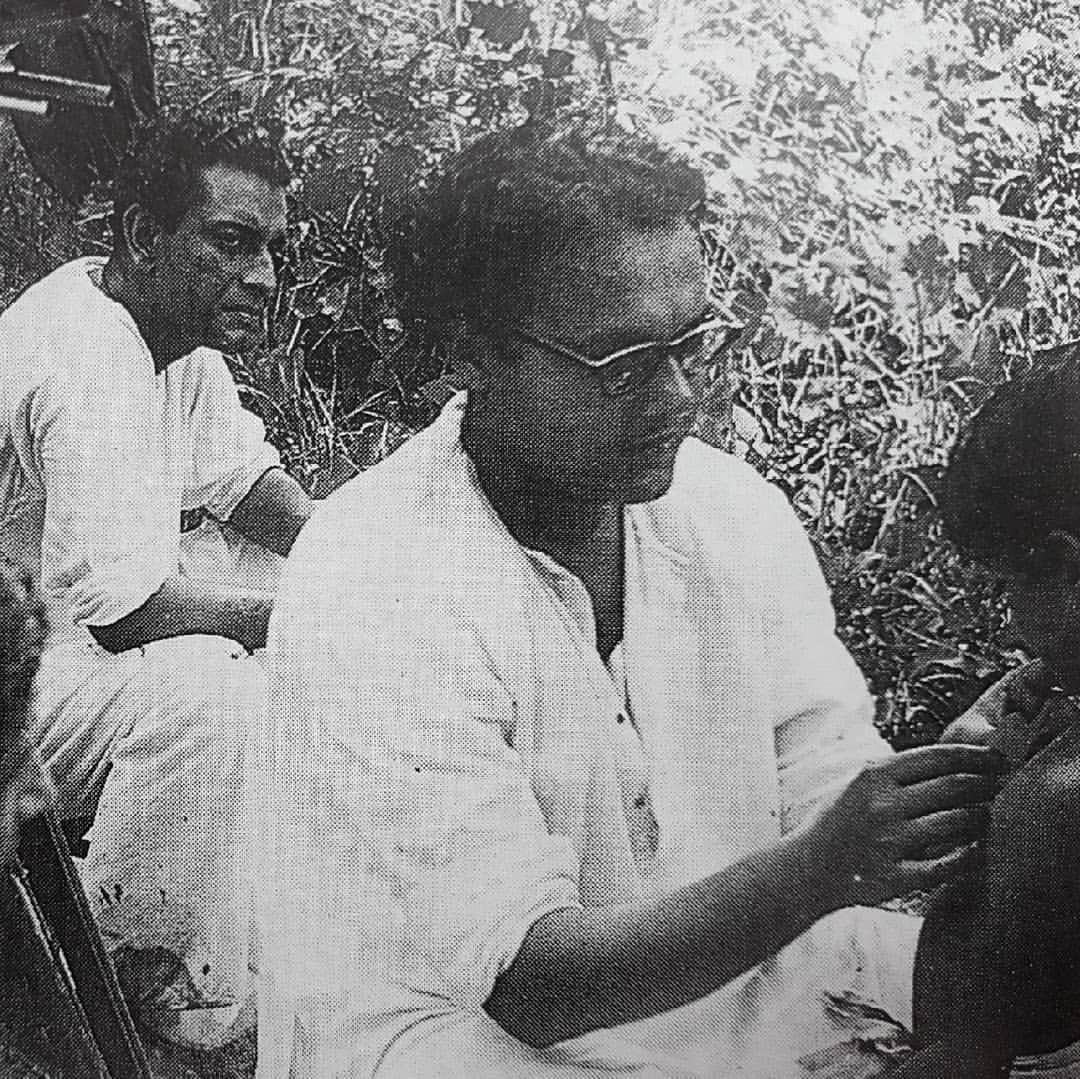

Pather Panchali (The Song of the Road, 1955) was shot over four years in chunks whenever Ray was able to find funds. In fact, for 18 months production shut down entirely until Ray’s mother talked to a friend of the Chief Minister of West Bengal who agreed to finance the remaining part of the film. Pather Panchali led to a collaboration with Ray which produced 10 films with masterful cinematography in 15 years.

The teaming of Ray, Mitra, Ravi Shankar, Dulal Dutta and Banshi Chandra Gupta was perhaps the greatest combination in Indian cinema. With a Michele camera, Mitra created wonders in Pather Panchali. The incomparable use of natural light during the monsoon rains, shots of the kash flowers and a running train in the distance created cinematographic magic.

Watch this analysis of the cinematography of Pather Panchali by Wolfcrow and witness the reason why it is a living resonance.

By the time Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1957) went on floors, the Arriflex camera had arrived in the cinematic world. Mitra made superb usage of bounce lighting during the indoor shots in Aparajito. Prior to Aparajito, bounce lighting was unknown to Indian cinema. Even the iconic Ingmar Bergman made use of this technique years later in Through A Glass Darkly.

Mitra can best be described as the perfect cinematic eye of Satyajit Ray. So well did he understand Ray’s thoughts, imagination and visualisation that his camera interpretation of them was sans any flaws. Apur Sansar, Jalshaghar, Devi, Teen Kanya – all of these Ray films bore the masterly Mitra stamp of cinematography. When Ray decided to shoot Kanchenjungha in colour, it was a challenge for Mitra. Without opting for too many special effects or cinematographic jugglery, he used close-ups to capture the panorama of the Himalayas. The montages were lyrical.

The first-ever freeze shot in Indian cinema was used to perfection by Subrata Mitra in Charulata. In this last scene of the film, Charu and Bhupathi’s hands are extended towards each other, but they don’t touch. This sequence of freeze shots has been hailed as a masterpiece in filmmaking.

Parting with Ray

To many, the true genius behind Satyajit Ray’s films like Devi and Jalsaghar lay in the finely textured cinematography that evoked empathy for the characters — a creation of Mitra, who fell apart after a 15-year-long association with Ray.

After Nayak in 1966, they parted ways. It was mainly due to creative differences. Mitra believed in certain visions that did not gel with Ray’s.

They drifted apart with dignity never criticizing each other in public. But Ray’s films after Nayak lacked the genius of Mitra’s cinematography. Mitra sans Ray was also not at his altruistic best. One of Indian cinema’s greatest tragedies.

Apart from his brilliant collaboration with Satyajit Ray, Mitra also shot four feature films for Merchant Ivory Productions in the 1960s – The Householder (1963), where he photographed most of the film with six photoflood lamps, Shakespeare Wallah (1965), The Guru (1969), which was the first Indian film shot entirely with halogen lamps and Bombay Talkie (1970). He also achieved much acclaim for his lyrical imagery in the Raj Kapoor-Waheeda Rehman starrer Teesri Kasam (1966), produced by Shailendra and directed by Basu Bhattacharya.

In The Householder, Mitra used tight close-ups of Shashi Kapoor and Leela Naidu, five in quick successions creating visual poetry. Raj Kapoor made sure Mitra cinematographed Teesri Kasam for Basu Bhattacharya.

The genius took a sabbatical from cinematography in mid-70s. He returned in 1986 to shoot Ramesh Sharma’s New Delhi Times. The shot of Shashi Kapoor running in a dream sequence as his newspaper office burns remains a lesson in cinematography.

Additionally, Mitra also composed music. His competence in playing the sitar was used by Renoir in a solo piece for the title music of The River, and by Ray for composing additional sitar pieces in Pather Panchali .

In the final years of his life, he was a visiting professor at the Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute, Calcutta, and a regular lecturer at the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune, where he won a set of admirers amongst the young. Till the very end he remained a champion of source-lighting, a technique of establishing the direction of light illuminating a shot in a film and, because of it, defining its visual logic and mood. His other commitment was to poetic realism, which he thought was the recipe for memorable cinema.

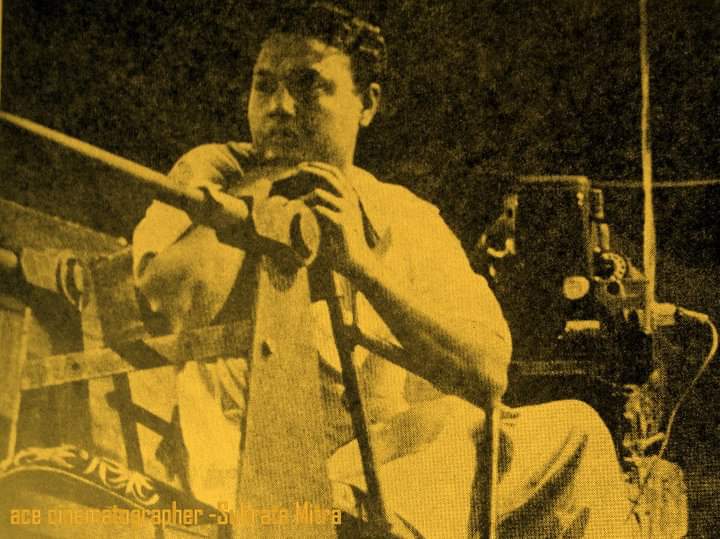

The Self-schooled Wizard of Cinematography

“Subrata Mitra mentioned to me that it was in nature and life around him that he found his inspiration for lighting. He’d always look for a natural source; a window, a skylight, a lamp and then use that to light up the scene. But more than lighting it was the quality of exposure, the texture of the skin, a fine eye for details that were an inescapable mark of films that he waved his wand over.”

Dev Benegal, a New York-based Indian filmmaker and screenwriter, most known for his debut film English, August (1994), which won the 1995 National Film Award for Best Feature Film in English.

Mitra made his first technical innovation while shooting Aparajito (1956). The fear of monsoon rain had forced the art director, Bansi Chandragupta, to abandon the original plan to build the inner courtyard of a typical Benares house in the open and the set was built inside a studio in Calcutta. Mitra recalls arguing in vain with both Chandragupta and Ray about the impossibilities of simulating shadowless diffused skylight. But this led him to innovate what became subsequently his most important tool – “bounce lighting” – and this a whole 10 years before Sven Nykvist claimed to be its originator in American Cinematographer! Mitra placed a framed painter white cloth over the set resembling a patch of sky and arranged studio lights below to bounce off the fake sky.

Jean Renoir often complained that cameramen often create lighting that doesn’t exist in the world and felt that they should, in fact, study how nature illuminates everything. This became the guiding force in Mitra’s work. He would almost always justify the lighting of a scene by simulating the source of light.

Rejecting the methods of studio lighting then accepted world-over, Ray and Mitra evolved the “bounce lighting”, which we take for granted today. Ray described it in an article – “Subroto, my cameraman, has evolved, elaborated and perfected a system of diffused lighting whereby natural daylight can be simulated to a remarkable degree. This results in a photographic style, which is truthful, unobtrusive and modern. I have no doubt that for films in the realistic genre, this is a most admirable system.”

In Ray’s films of the 1950s, he developed the Arriflex-Nagra combination, for image and sound, respectively, which later became the standard film equipment in India. In the early 1960s, while shooting Ray’s Devi and Kanchanganga he dispensed with bounced lighting and developed instead a soft light system in Charulata to achieve the same quality. He also pioneered the use of halogen lights for shooting The Guru .

In the days before instant video monitoring, instant video replay and digital gizmos, cinematography was the dark art and the cinematographer its wizard with the array of secret charms and spells he could bind us in.

When Mitra started watching films in the 1940s and 1950s much of Indian cinematography was completely under the influence of Hollywood aesthetics which mostly insisted on the ‘ideal light’ for the face using heavy diffusion and strong backlight. But according to Mitra, Hollywood also had rebels like James Wong Howe who was able to separate the foreground and the background with careful lighting in films like Come Back Little Sheba (1952) and The Rose Tattoo (1955). Some other films which have inspired Mitra include Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story (1948), Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950) and Alfred Hitchcock’s I Confess (1952).

“Subrata Mitra was obsessive about details. ‘God is in the details,’ he would say quoting the architect Mies van der Rohe and also echoing what Satyajit Ray said, ‘It’s details that make cinema.’ It was the attention to detail that made Subrata what he was. On an Indian Airlines flight, he took a white plastic cup cut it in half, fitted it onto his still camera converting it into an incident light meter. It was as accurate as the professional one he had which cost him over $400! In many ways, he was a techno-geek before they were even invented.”

Dev Benegal

However, Mitra did not believe, that the excellence of a film is “terribly dependent” on its technical quality, because “it is not the lens in the camera that really matters but the eye at the other side of it.” This faith in the supremacy of the artist over his artefact has been borne out amply in many of his films. His use of dolly shots, e.g., in the sequence of Durga’s death in a stormy night (Pather Panchali), of varying cinema angles with limited number of cameras, e.g., in photographing the ghats of Varanasi in Aparajito , and the jerky camera movement in New Delhi Times , will remain examples of excellent cinematography by any standard.

“The indirect lighting source that he created offers a large surface, so, if you wanted to catch a certain amount of light, it would reflect back on the subject —soft and enveloping — as you would see in Teesri Kasam.”

Mahesh Aney, National Award winner cinematographer of Swades, says that Mitra’s invention has become part of the filmmaking gene, no one can escape it.

James Ivory (one half of the Merchant Ivory Production with which Mitra collaborated for four films) writes: “When I first began to make full-length feature films – this was in India in the early 1960s – Subrata Mitra became my cameraman and, therefore, my eyes through which I was able to see or imagine the world of my films. This was not really his world – the stories I wanted to tell then with Ruth Jhabvala and Ismail Merchant were very different from the ones he had created with Satyajit Ray. Perhaps, however, he finally felt as grateful to me for taking him a little way into our own world as I did to him for helping lead me there. Subrata soon became more than my eyes: when I made The Householder with him in 1962, I’d never directed a theatrical feature and, to tell the truth, whatever I might have learned about how to do that at the University of Southern California Film School had gone in one ear and out the other. On the first day of shooting, he asked me to show him the shot division of the day’s scene and I said, absolutely innocent, “What’s that?” Subrata took a puff on his cigarette, narrowed his eyes a bit, and sat down with me to dissect the scene into proper shots: masters, medium shots, close-ups, etc. So he must have sat hundreds of times with Ray, the difference being that it was mostly Ray, I imagine, who told Subrata how the day’s work would proceed. But instruction is instruction, and I could not know in my ignorance that the collected skills and wisdom of two masters, both Ray and Mitra, were by some miraculous and lucky twist of fate being passed on to me. I think I have never entirely left those lessons behind, nor do I ever want to. Today – two continents, four decades and any number of other gifted cameramen away – when I prepare my own shot divisions (mostly in my head, it must be said) it is still Subrata’s spirit which stands behind my shoulder, urging me to combine this or that for reasons of visual and editorial elegance (usually having something to do with light, real or artificial) – or just for fun, or maybe because there’s a new and interesting piece of equipment with which to experiment.”

Official recognition came very late to this pioneer of Indian cinematography. Subrata Mitra won the National Award for his work in Ramesh Sharma’s fine political thriller New Delhi Times (1985), one of an array of awards he has won including the Eastman Kodak Lifetime Achievement for Excellence in Cinematography in 1992.

It is indeed a pity that his career was limited to twenty feature films – fifteen in B/W and five in colour and three documentaries. Filmmakers, young and old were afraid to approach him because of his grave, and on occasion, forbidding appearance and of course his principled attitude. His work was however greatly appreciated abroad, particularly by the French.

“Unfortunately, our bloodstream has this narrow mediocrity, which does not allow us to appreciate the genius in others, it’s a pity that we did nothing to commemorate Mitra’s genius.”

Bijon Dasgupta, art director of about 150 films recalls Mitra for his genius in light as well as for his legendary temper, who would neither take mediocrity nor nonsense.

Subrata Mitra was perhaps the greatest ever Indian cinematographer, who revolutionized prevailing aesthetics in Indian Cinema with innovations designed to make light more realistic and poetic. His work set a standard that others could hope to equal or surpass but, regrettably, none did in this country in the last 47 years. It is our shame that while our film history has been extremely kind to Satyajit Ray, it has, in equal measure, been unkind to Subrata Mitra.