“A flat-out masterpiece,” “the most important film of the year,” “a wild wild ride,” are only a few accolades that Parasite has earned from the critics who just can’t stop raving about it, and this Korean film might have grabbed your attention recently after it won the Best Subtitled Foreign Film at the 77th Golden Globes.

Ending up as No.1 in quite a lot of critics’ year-end top-ten lists, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite (‘Gisaengchung‘) became the second foreign film to ever be nominated for Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture since the 1998 film Life Is Beautiful. It was nominated for three awards at the 73rd British Academy Film Awards: Best Film, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best Film Not in the English Language. It is the first Korean film to receive nominations at the British Academy Film Awards (except for Best Film Not in the English Language).

The film is so popular that the North Korean government is using its depiction of poverty as propaganda. And the movie made history as the first South Korean submission to be nominated for the Best International Feature Film at the 92nd Academy Awards (which it is very likely to win), as the category has been renamed this year. Despite a booming film industry that has produced international successes for decades, no South Korean film has made the cut with the Oscars. Parasite has also been nominated for five other Oscar categories, namely, Best Production Design, Best Film Editing, Best Original Screenplay, Best Director and even Best Picture!

So you might be wondering what all the fuss is about. This buzz surrounding Parasite began back in May when it won the prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, becoming the first South Korean film to do so. It then blazed through the international festival circuit, selling out screenings at Telluride and the Toronto International Film Festival, and flooring audiences at Fantastic Fest and the New York Film Festival.

It could be argued that in the age of Netflix series and billion-dollar superhero spectacles (not trying to get into another Scorsese-like controversy though!), the cultural zone, formerly known as “world cinema” exists mostly as an echo of itself. But that’s not the case about Bong’s films. There’s nothing ghostly about them. They are vibrant genre mashups, loaded with ideas and lustrously crafted, blending elements from Hitchcock, Tarantino, European art film, and the melodramatic and violent traditions of Korean cinema, which remains largely unknown in the American films.

This film is a companion piece to Bong’s 2006 smash hit The Host, Bong’s twisted tale of eco-mutation (host and parasite, get it?), which saw a similarly bankrupt family battling a monster from the deep. This time, however, the family is the monster – a four-headed beast that operates as a single entity and shows little mercy to outsiders.

Parasite is essentially a tale of two families, the Parks, who live in a designer house atop a hill, and the Kims, who live in a grungy basement apartment across town – literally high and low, both physically and in social status, they wouldn’t normally meet.

But then a friend drops by the Kims’ basement with a gift, a big stone that his grandfather claims will bring the family material wealth. “This is so metaphorical,” says Kim Ki-woo.

The friend also brings word that the wealthy Park family needs an English tutor for their daughter, and he sets up Ki-woo with an audition for the job.

It’s this job that kicks the plot into motion. Ki-woo finds quite a fan in his student, the teenage Da-Hye (Jung-Hye) who crushes on him instantly. The young man is more seduced by the wealth and lifestyle of his employers. His wife, Yeon-Kyo (Cho Yeo Jeong), is so impressed by the boy’s teaching abilities that she mentions her need for a tutor to improve the painting skills of her younger son, Da-Song (Jung Hyeon Jun). Ki-Woo recommends Ki-Jeong without telling the Parks she’s his sister.

Soon the plan escalates. Why not have his mother replace the Park’s live-in housekeeper (Jeong Eun Lee), by whatever sinister means necessary. And who better than his dad to replace the family chauffeur behind the wheel of the Mercedes? It’s not long before the Kims, pretending not to be related, have basically occupied the Park household in a military-like coup. As the caption of the film suggests, they “act like they own the place.” It’s a home invasion on an insidious scale.

And then? Well, what I can say about the film without spoiling much is – though it starts as a class-conscious satire, it ends as a gory portrait of a world at war with itself.

As the title of the film suggests, the Kims almost seem to be obeying the rules of natural selection: The host organism reveals a weak spot that licenses infection; the parasite takes advantage and invades. The Kims feel no malice toward the Parks, at least not at first; a parasite is ruthless and completely self-interested, but not intentionally cruel. After all, if it destroys its host, it cannot exist on itself. But are they the real parasites in this world? Initially, it might seem so, but let’s get back to that later.

The script for Parasite is one of those clever twisting and turning tales for which the screenwriters should get the credit (Bong and Han Jin-won, in this case). But this also is very much an exercise in visual language that reaffirms Bong as a master. Working with the incredible cinematographer Kyung-pyo Hong (Burning, Snowpiercer) and an A-list design team, Bong’s film is captivating with every single composition.

The social commentary of Parasite leads to chaos, but it never feels like a didactic message movie. It is somehow both joyous and depressing at the same time. It is so perfectly calibrated that there’s pure joy to be had in just experiencing every confident frame of it, but then that’s counteracted once we start thinking about what Bong is unpacking here and saying about society, especially with the perfect, absolutely haunting final scenes.

“That’s a Metaphor!”

Twice in this acid black comedy, characters exclaim “That’s a metaphor!” about something they’re looking at — which can be seen as Bong poking fun at himself (as if Wes Anderson’s characters were to announce that they live in a big dollhouse!) The South Korean director thinks in metaphor. It’s his forte. Consider the first shot of Parasite (the title itself is a metaphor): what looks to be an empty birdcage draped with socks in front of a window that’s partially below street level.

In this apartment, all dreams of flight have been extinguished (the socks reinforce the connection to the dirt), while the Low Vantage shot indicates exclusion — mocking the residents, the destitute Kim family who have their view blocked by a drunken man pissing against a wall. Stuck underground, they crawl over the depths to which they’ve sunk, over their lack of connection. This is beautifully portrayed as they press against the ceiling to try to get a Wi-Fi signal from upstairs. They desperately need to attach themselves to something high off the ground.

On one hand, what happens to the Kims — who are so poor they literally live underground, in a rancid-smelling, insect-infested apartment just below street level — has the quality of a fairy tale. Ki-woo’s magical friend not only gives him a job, and a point of entry into an otherwise inaccessible world of wealth and privilege, but also a traditional stone carving that is supposed to bring prosperity. But on the other hand, all these things are metaphors: The underground apartment, the stinkbugs, the disappearing American friend, the rich princess locked up in a castle, and the stone carving, which brings nothing good to anyone but eventually works its way into the plot, in a gruesome and ironic fashion.

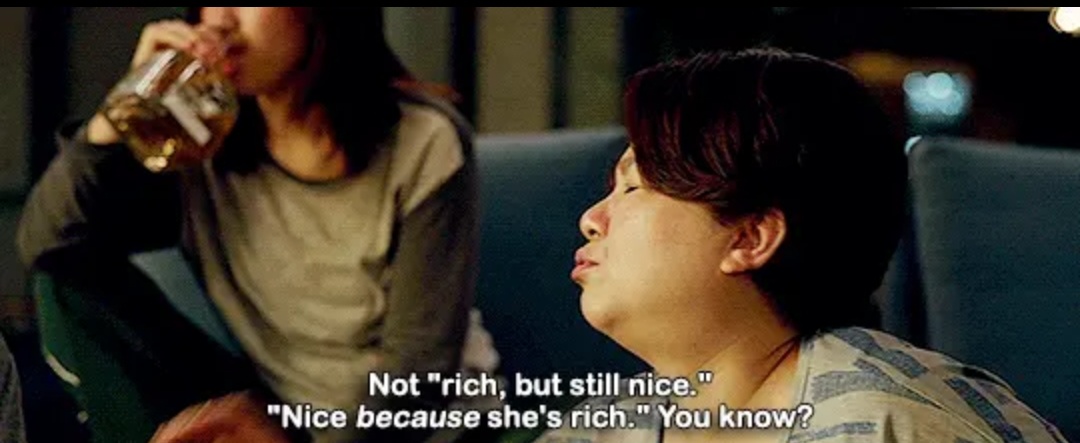

“Money is an iron. It smooths out the wrinkles”

Another metaphor and a clue that the Kim family’s scam, which just seems funny at first, is more than it appears.

Bong Joon-ho never goes for just funny. His sci-fi epic Snowpiercer, for instance, put the last survivors of a climate disaster on a train and set them to kill each other in a class war. And as the comedy starts curdling in Parasite, we can smell the stench of class struggle again.

“A Comedy without Clowns, a Tragedy without Villains.”

Well, that’s what Bong calls his own film. So what sort of movie is this? It’s not a home-intrusion thriller, like “Unlawful Entry” (1992) or “Panic Room” (2002), though it’s often tense at times. It’s not a comedy of social upheaval, like “Boudu Saved from Drowning” (1932), though it does have some wit to spare.

And it’s not a horror flick either, despite a passing resemblance to Jordan Peele’s Us, released last year. Like Peele, Bong makes the eerie suggestion that the underclass might literally exist below our feet.

Bong is comparably resourceful on his own behalf, combining many storytelling traditions into a style all of his own. Parasite is not a genre movie, but it occasionally employs — carefully and deliriously — genre conventions and all the assumptions that come with them. You keep expecting Parasite to turn into one thing, but it keeps turning into something else. It mutates, like a real parasite trying to hang on to its host, the viewer.

But there is an unanswered question hanging over this film from the beginning (and unasked too), which drives it through various plot twists toward a violent climax: Who or what is the real parasite in this ecosystem? The Poor who attach themselves to the Rich or the Rich who suck the marrow of the Poor? Or is the system itself the parasite, drawing its energy from the turbulent interaction between the Rich and the Poor?