After making 10 feature films, released over a quarter-century of filmmaking (his debut, Kicking and Screaming, came out in 1995; his other films include The Meyerowitz Stories, The Squid and the Whale, Greenberg, and Frances Ha), this, at last, is Noah Baumbach’s breakthrough in the dramatic genre. Marriage Story is truly a work of an artist, built around two bravura performances of incredible sharpness and humanity, who turn this tale of divorce into a Kramer vs. Kramer for the 21st Century.

A film nominated for six Oscar nominations – Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actress, Best Original Music Score, Best Original Screenplay – Marriage Story is a film about divorce: how it operates, what it means and its larger consequences. It’s about two people coming to terms with a process that, however necessary, is more wounding at times than their heartbreak.

As the movie opens, we hear the voices of Charlie (Adam Driver) and Nicole (Scarlett Johansson), who’ve been married for 10 years and have an 8-year-old son, Henry (Azhy Robertson). As the two take turns describing what each one cherishes about the other, their lists are accompanied by a montage of moments from their domestic life, staged with such casual detail — the way Charlie brushes the hair off his nose as Nicole gives him a bathroom haircut; the way she leaves her Zabar’s and Pink Freud mugs standing around with tea bags in them; his face-stuffing; her jar-opening; the family’s hyper-competitive Monopoly games — that though we don’t even know these characters yet, you smile with recognition. This montage tells us something vital, that Charlie and Nicole have never stopped loving each other, and makes us ask the question that why are they getting divorced? Why couldn’t they work it out?

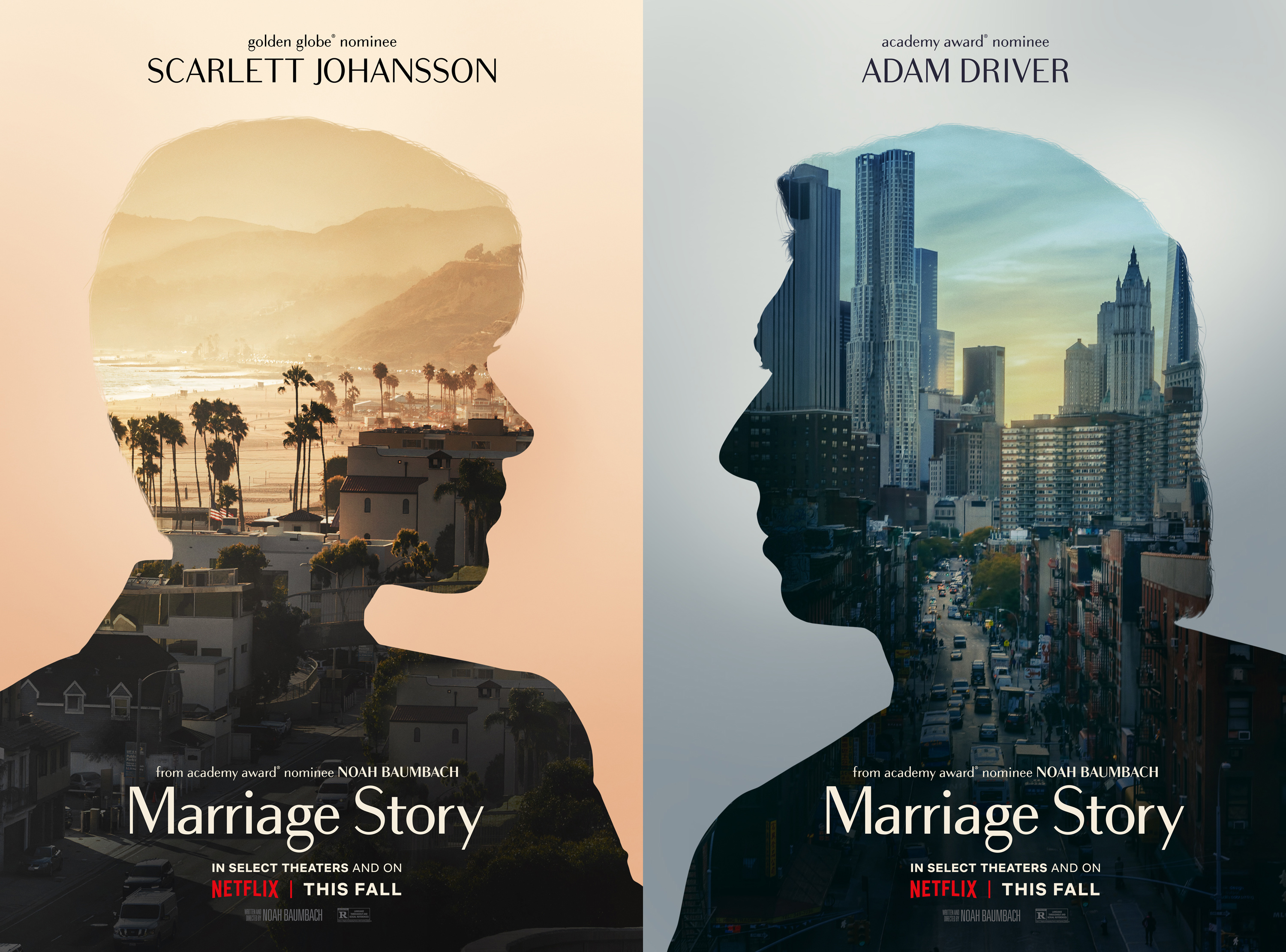

It’s Nicole who has instigated the split. She’s an actress, raised in Los Angeles, who had a burst of popularity from a romantic comedy “All Over the Girl”, and then, after falling in love with Charlie, moved to New York to marry him and become the star of his downtown experimental theater company. They were in their twenties, gifted and successful, and once their son was born they created a nice life in Park Slope. As far as Charlie is concerned, he’s living the dream. But Nicole had periodic thoughts about relocating to L.A., which Charlie “discussed” but never took seriously. That’s because he’s a New York guy. Besides, his troupe is based in New York, and he directs the shows, including an Electra that’s headed to Broadway. How could they possibly move?

Nicole, however, now has the chance to star in a TV pilot that could lead to a series. And what she realizes is that though she loves her family, she has spent the marriage living Charlie’s dream, putting hers on perpetual hold. Baumbach has captured how personality and ego can add up to one stubborn roadblock. There’s a telling moment when Charlie, the avant-garde dynamo, reminds Nicole that he doesn’t watch television, as the camera flashes over to a glimpse of the “cool” horror movie he’s watching instead. His dismissal of “television” diminishes the core of Nicole’s career.

Both agree that they need to talk but don’t know how to start. And that’s what the job description of this movie reads, and Baumbach, whose skills as a screenwriter have rarely been this acutely hilarious and heartfelt, straps in Charlie, Nicole and the audience for an emotional rollercoaster ride that climbs and dives from bursts of laughter to sudden tears.

Even though the scales of empathy are tipped towards Nicole, there is a common enemy, and that’s the lawyers. It’s entertaining as Baumbach portrays them as representatives of evil – it’s a job that involves looking for the worst in good people. Nicole retains the services of Nora (Laura Dern), a glamorous LA legal assassin. In one sublime monologue, she even suggests that she would even have a solid line of argument if it came to Mary suing God for parental rights to Jesus.

Charlie, meanwhile, hires Bert Spitz (Alan Alda) whose passive battle technique ends up getting him nowhere. So in comes Jay Marotta (Ray Liotta), who is willing to play Nora at her own game, and it’s knives out all the way. Even though the pair claimed to want an amicable break, Charlie is unable to accept that his demands for Henry to return to New York are not acceptable to Nicole, and so matters almost naturally drift towards ugliness.

This is hardly the first time Baumbach, has steered us through the emotional wreckage of a broken marriage, as he did 14 years ago in The Squid and the Whale. That picture was sharply drawn from elements of his parents’ divorce, and Marriage Story, though not explicitly autobiographical, has already provoked comparisons with Baumbach’s own.

It’s been reported that he used his own divorce from actress Jennifer Jason Leigh as an inspirational spark for this story. His directorial choices are unerring, from the dynamic cinematography of Robbie Ryan and the intelligent editing of Jennifer Lame to the grace notes that spreads through Randy Newman’s score.

Still, Marriage Story lives and breathes through its superlative actors. As Henry, the son caught between the parents he knows and the legal system he doesn’t, young Azhy Robertson offers a touching portrait of a confused child going through the collateral damage of his parents’ divorce.

Scarlet Johansson, temporarily liberated from the MCU (her solo Black Widow movie will be out in March), reminds us that the dramatic heights she scaled in Ghost World, Lost in Translation, Match Point and Under the Skin are still very much accessible. Her monologue on how her marriage gradually made her feel “smaller and smaller” is deeply moving, and yet is packed with humour (a subtle nod to Meryl Steep’s monologue in Kramer vs. Kramer). Johansson has never been better or more emotionally expressive than she is as Nicole.

Above all, this is Driver’s shining two hours, ranking him with the finest actors of his generation. Charlie is self-involved and immature at times and yet a man full of warmth. The actor, more popular as Kylo Ren in the Star Wars universe is also the incendiary artist who’s been killing it on TV (Girls), stage (the recent Broadway revival of Burn This) and screen (BlacKkKlansmen, Silence). Marriage Story is a jaw-dropping demonstration of Driver’s range as an actor.

The first half ends with quite a few questions on your mind: Do the lawyers manipulate and lie with Nicole, who seems to have sacrificed and suffered more during the marriage? Or with Charlie, who has far less family support and seems far likelier to be the director’s onscreen substitute?

Baumbach refuses to provide an easy answer. Maybe that’s a sign of his integrity. His writing has rarely been more incisive, and it has almost certainly never been more forgiving. Nicole’s aggressive legal strategy may strike you as too calculating, unless you understand it to be a long-overdue act of reclamation by a woman tired of putting her own needs and dreams aside.

Yet Baumbach, with his delicate touches, proves that love persists, even when the law comes in the way. As Nicole and Charlie sit uncomfortably across a table with their lawyers wrangling, she doesn’t think twice before ordering him his favourite Greek Salad (when he was having trouble making sure what to order). For Charlie, it only takes a call to land up at her doorstep in the middle of the night to fix her jammed gate, and Nicole gives him a haircut just the way she has always done. All of this takes place during the legal process of their divorce.

Even when they are screaming the place down, she rolls out “Honey!” all too easily. The most powerful scene of the film is where all their bottled-up anger breaks out in the form of shockingly foul words. Charlie, realizing it immediately, falls to his knees. Nicole reaches out and touches the top of his head.

A range of emotions swells up after watching the last scene as Nicole calls out Charlie (who is leaving, holding their son in his arms), runs up to him and non-nonchalantly ties up his shoelaces.

Driver’s performance does achieve the deeper, more lingering impact, in part because he is granted the courtesy of more screen time, but that may well be because his character has more growing to do.

And so he does. Toward the end of Marriage Story, Nicole and Charlie both sing numbers from Company, Stephen Sondheim’s 1970 musical about marriage and its dissatisfactions. These are richly textured frames of two people who have been steeped in the arts. But it is in the unforgettable moment when Charlie launches into his solo (“Someone to hold me too close/Someone to hurt me too deep/Somebody sit in my chair/And ruin my sleep/And make me aware/Of being alive.”), you’re seeing a man who has managed to embrace his pain and feel more alive and hopeful. Driver, Johansson and Baumbach bring you to your knees through the hard truths of life and relationships, and deliver the indelible true meaning of being alive.