“The great danger of lying is not that lies are untruths, and thus unreal, but that they become real in other people’s minds.”

The first words of “Caging Skies”, a novel by Christine Leunens, which Taika Waititi’s latest feature Jojo Rabbit is adapted from.

When you put the words “Hitler” and “comedy” together in a concept, you are walking on dangerous grounds. In this regard, director Taika Waititi (Boy, Hunt for the Wilderpeople, Thor: Ragnarok) is in good company. The British government was very concerned about Charlie Chaplin making The Great Dictator in 1940; Ernst Lubitsch raised some eyebrows when he made To Be or Not to Be in 1942. Mel Brooks has twice met trouble with The Producers and his remake of Lubitsch’s film (“Springtime for Hitler,” the scandalous musical number from The Producers, was once the cutting edge of black comedy.)

Depictions of Hitler as the butt of satire tend to upset some people, regardless of intent. It’s an audacious, challenging form of comedy. We can assume that Waititi, the son of a Maori painter and a Russian Jewish mother, knew exactly what he was doing when he decided to write the script, adapting “Caging Skies,” a 2004 novel by Christine Leunens (though the tone in the novel is entirely different). If you know Taika Waititi’s work (including the vampire mocumentary What We Do in the Shadows), you know that humor is his preferred form of expression.

The movie has gone on to win the Toronto International Film Festival People’s Choice Award (Taika Waititi), Writers’ Guild of America for Best Adapted Screenplay (Taika Waititi), Critics’ Choice Award for Best Young Performer (Roman Griffith Davis) and British Academy Film Award for Best Adapted Screenplay (Taika Waititi). It has also been nominated for Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Actress in a Supporting Role, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Costume Design, Best Production Design and Best Editing at the Academy Awards 2020.

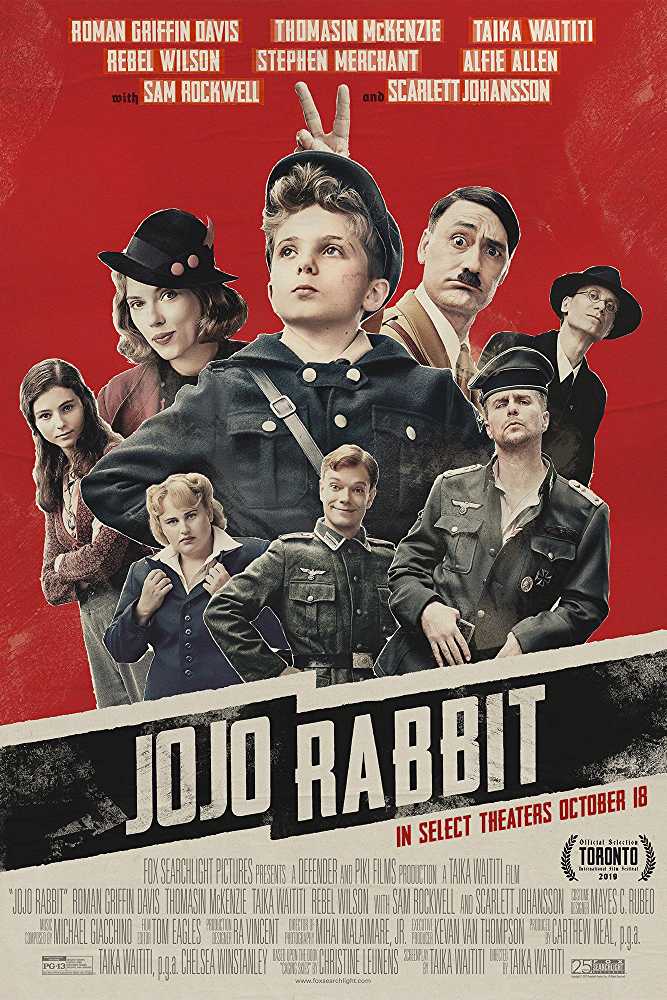

Centering on a conflicted 10-year-old boy, Jojo Betzler (Roman Griffin Davis) and his loving mother (Scarlett Johansson), Jojo Rabbit looks at Nazi Germany’s anti-Jew world view and aims to take away its power through relentless mockery.

It’s the waning days of World War II and the Allies are close to defeating Hitler’s army, yet Jojo remains blindly fanatical to the cause. He goes to Nazi youth training weekends, which involve burning books and throwing hand grenades, but he’s bullied because of his small size and lack of a killer instinct. Jojo’s main confidante is Adolf, his hero come to life as his imaginary best friend.

Alone at home one day, Jojo finds out his mother’s biggest secret: she is hiding a Jewish girl, Elsa (Thomasin McKenzie), behind a wall in the bedroom of his late older sister.

This blows the kid’s mind since he’s been taught that Jews are monstrous, mind-reading devils who should be hunted down. Instead, Jojo is drawn to Elsa’s fiery strength – as he and his mom also grow closer. He faces a major dilemma – should he turn the Jew in (something that Adolf would praise him for), though he knows doing so would threaten both him and his mother.

Johansson really shines in her role as a loving parent who has her adorable eccentricities yet tries to keep Jojo from growing up too fast.

The youngsters are stellar as well. Davis, whose huge eyes take in everything around him with increasing alarm, is impressive in his professional acting debut, and Archie Yates is a hoot as Jojo’s “indestructible” pal Yorki.

McKenzie, more of a known face because of her work in last year’s excellent Leave No Trace, does similarly deft work as Elsa, who starts off having great fun playing a ghost to scare Jojo, only to affectingly twist their relationship into something deeper and more painful.

And then there’s the movie’s satirical trump card. Waititi, himself (sounding like a mean-girl avatar of the Führer) keeps popping up as a goof-head version of Adolf Hitler, who speaks in aggressive anachronisms (“That was intense!” “I’m stressed out!” “Correctamundo!” “That was a complete bust!” “So, how’s it all going with that Jew thing upstairs?”),

This is where Waititi’s genius comes through. He’s all witty and weirdly appealing at first, yet as Jojo turns more of his attention toward Elsa, Hitler subtly transforms into the petty, angry monster from the history books, with Waititi exhibiting the dramatic real-life mannerisms of the infamous dictator.

The problem for some critics is perhaps because the film makes us laugh at a subject that usually comes packaged as a tragedy. Waititi depicts Hitler as a manic, out-of-control, childish version of the Fuhrer, but that’s exactly what a confused 10-year-old conjure from his own trauma.

And it’s incorrect to say that Waititi doesn’t have a serious purpose. The film gets darker as it goes, becoming more confronting and nerve-racking. It’s no crime to believe that comedy can be every bit as serious and engaging as drama; indeed, the recognition of that potential is well overdue. Comedy used to be much more nuanced and subtle than it has become. Today’s comedy rarely delves deep into problems of the human condition, but that’s what the greatest comedies have always done. The best example? Well look below, and take a bow.

The supple nature of Jojo Rabbit and Waititi’s control of the changing mood is one of the picture’s great assets. This is where the true power of comedy lies. Being the most malleable genre, it just doesn’t make people laugh, it makes them laugh and cry in the very next beat.

Hail Waititi for bringing intimacy and passion to each step in the boy’s journey, while fighting a satirical war against hate. Heil him, man!