“Less is more.”

That’s the art of minimalism – to speak less and say more.

Indraadip Dasgupta has been a celebrated music director in the Bengali film industry for two decades and has scored some of the best-known songs over the years. But it was the call of the spot behind the camera that he has not been able to ignore. In his directorial debut, he has shown exceptional potential in dealing with a sensitive subject and creating a heart-warming film out of it.

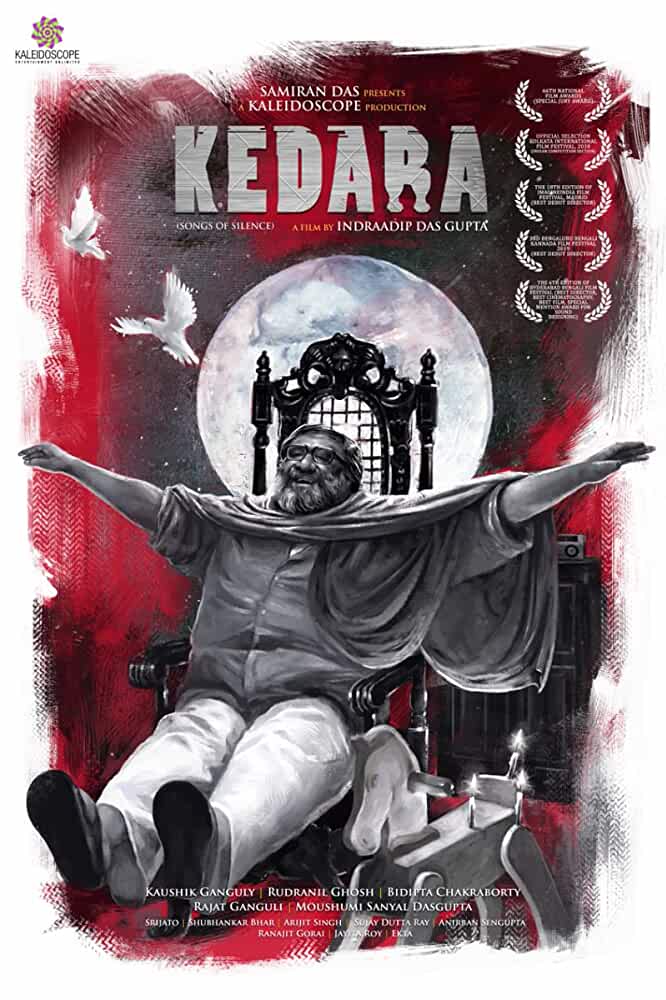

Kedara – a film that does not fit into any genre classification at all and perhaps could be placed into its own genre. It was screened at various film festivals – national and international – and also bagged this year’s Special Jury award at 66th National Film Awards.

For Kedara, the underpainting is very simple. Narasingha is a jaded, defeated ventriloquist who lives in a dimly-lit house in Kolkata all by himself. Narasingha seems to possess problems of delusion, and is usually meek and soft-natured in his day-to-day life. Never saying a word against those giving him a tough time, he walks through life with a particular sense of detachment, until the arrival of an easy piece of furniture in his barren and eventless existence turns his life around and provides him the self-respect and self-love that he needed so badly

This plotline is the simple initial layer of paint, that the director uses as a base for subsequent layers of loneliness, psychology, social identity, and art.

Kedara perfectly captures the fact that there is literally nothing happening in its protagonist’s life. In that sense, Srijato Bandopadhyay’s script is apt for a story such as this, in that it dwells on the seemingly insignificant aspects of Narasingha’s life: how he shops for fish, or ogles his house-maid, or kicks aside an invisible pebble in his path, or ignores cat calls and wolf whistles by the loafers of the neighbourhood, so on and so forth.

“The basic idea came a few years after I started living alone. There are always both positive and negative attributes to living away from one’s family and being unmarried — you learn to live in a new way, adjusting with the lone world. I go back to a vacant house, but I am not lonely. The ‘me time’ I got, let me be more in the realms of imagination and come up with many human story ideas, with Kedara being foremost among them.”

– Indraadip Dasgupta

The name of the protagonist – Narasingha is a metaphor. It’s the 4th avatar (reincarnation) of Lord Vishnu, a form of part lion and part man (nara means man, singha means lion). The two halves of the name are reiterated as the two halves of the film. The armchair (kedara) being the object which transforms the character to bring out his fierce traits.

Narasingha’s only confidante Keshto (played wonderfully by Rudranil Ghosh) sells antiques opposite his house. He feels he is as useless as the old collection in his shop. Much like Narasingha, he, too, finds solace and a home amidst his collection.

It is always good to see Rudranil Ghosh in roles different from the stereotypical ones he usually gets. He plays a cowering man with a deep affection for Narasingha, whom he genuinely considers his big brother. Without ever trying to intrude in his Narasingha’s secret world, he understands the beautiful soul he carefully guards from everybody.

Since loneliness forms the foundation layer in this film, let’s understand the philosophy and psychology behind this state of mind.

Loneliness is universal and necessary. We need not be aware of it all the time, but it is always there, lurking in the background. Human life inevitably takes the form of a struggle against loneliness. We reach out to others in order to avoid sinking into complete isolation. However, although they might provide us with some degree of consolation and a connection, our loneliness is something that can never be overcome.

Ben Lazare Mijuskovic, PhD, MA, professor of philosophy and humanities at California State University

In philosophy, there are two schools of thought that I have come across about loneliness, and this film touches both of them. One of them believes that loneliness is not the lack of company, it is the lack of self-purpose.

Till the pivotal point in the film when he sits on his “kedara” for the first time, Narasingha is falling into an abyss of melancholy and anxiety in an environment that left him feeling numb and miserable.

That Narasingha is a ventriloquist is revealed in the most unexpected fashion. Narasingha does not only mimic sounds or voices; the voices have their own entities for him and they live with him — they are his family.

To give himself a false sense of hope, Narasingha mimics the ringing of his residence’s telephone that has now been long dead, In perhaps one of the most tragic tracks of the story. But at the same time, he is not entirely detached from the reality around him, which is why, when he answers the call and no one speaks, he gets irritated, and wonders who is bothering him over and over again. In doing so, he creates a grand delusion around him that wallows in self-pity but keeps him going at the same time. He keeps reminding himself that it is not his fault, and this keeps him alive.

So is he really lonely? Can you really be alone if even in your imagination you are surrounded by your loved ones? Or is there a subtle difference between feeling lonely and being alone? Of course there is.

Another theory that suggests that there is, to an extent, an art in loneliness; and it could be a valuable step to actually find self-purpose.

There’s a moment in the second half of the film where Narasingha is sitting on his “kedara” and throws all his masks, one by one, into the fire.

The chair, in itself, acts as a metaphor for redemption for the Narasinghas of the world. It could have been anything — a pen, a memory, or an emotion. In Narasingha’s tale, it is a high-back armchair. It is from this moment when he gets the chair, that the film steps back from its realism and steps into magic realism in a rather extraordinary way. The armchair, once regal-looking but now an antique that has seen better days, comes along with a mirror and fits neatly within the ambiance of the home Narasingha lives in.

“Experiencing a state of mind where it’s only you and yourself gives you the access to explore yourself mentally and physically as a person, providing you a different perspective on who you are as well as a new cognitive relationship in your identification with the world.”

Lewis Hyde in his introduction to Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. In exploring the context of Rilke’s letters, Hyde provides insight into how the writer embraced his solitude as means of “poetic practice” and how he turned what’s known as a “curse into a blessing.”

Kedara is a one-man show. Veteran actor-director Kaushik Ganguly is nothing short of superlative in the best performance of his career. He was bestowed the prestigious Hiralal Sen Award for Best Actor for his performance in the film at the 24th Kolkata International Film Festival.

It is difficult for any actor to carry an entire 108-minute film on his shoulders with the other characters offering cameos. But he does it so well that we get sucked into the story as if it is ours.

Not a single gesture is overdone, not a single laugh or frown is out of place. Kaushik Ganguly’s understanding of his character’s bruised pride is visible not so much in the way he performs the bits in which the forgotten artist is talking about his tragedy, but more so in the way he navigates the silences. Narasingha’s loneliness, his fond memories of his grandmother, his remembrance of the wife who has left him, and his relationship with Keshto, all come together beautifully through Kaushik Ganguly’s performance.

Though one must take one’s hat off at Indradeep whose directorial debut Kedara is, he might never have been able to turn the film into what it has finally become unless Koushik Ganguly had lived the character of Narasingha not forgetting the fact that Kaushik himself mimicked the “voices” in the film.

Kedara wouldn’t have been made if Kaushik didn’t agree to play the role of Narasingha. It’s not only his best performance, but he has also, in fact, outdone himself in this grey character of a simple man, who is always in a state of flux.

Indraadip Dasgupta on Kaushik’s performance in Kedara

Even in the technical aspects, the film is exceptional. The foley work, the make-up, the editing, the sound design, the cinematography are top-notch.

Cinematographer Subhankar Bhar and editor Sujoy Dutta Roy have a lot of contribution in making the film an ensemble experience. Since the film is largely performance-based, the most poignant moments on screen are the close-range shots of Narasingha’s expressions. A shot of pigeons playing in a ray of light that has peeked through in the dark room while Narasingha playfully feeds them offers the first glimpse into the heart of the man who is good for nothing in the eyes of the world.

There is a sense of ‘storytelling’ in the camerawork throughout, which retains the intrigue around the story till the end. The colour tone of the film is mostly dark, but the grey tones do not hinder the flame of hope that runs like an undercurrent through the film. The camera invites you to journey with this man and you empathize with this man.

Arijit Singh’s minimal background score is synchronized very well with every sequence. The entire cinematic experience proves that Dasgupta could transport his vision and perspective to each and every department of the film.

Lastly, the film speaks volumes about the dying art of “harbola”. Through Kedara, the director celebrates souls that only wish to be happy and are in tune with nature, like the song of birds or the flow of rivers.

In a city of screeching buses, blaring horns, and a million other sounds of urban cacophony, there are still some men who know birdsong. With years of training that have perfected their art, these men can imitate the sweet call of the koel or the rough cawing of a crow. From dogs and cats to planes and cooking food, their imitation of real sounds – both familiar and exotic – will leave us in awe. Though we can call it ventriloquism, it is said that there is no correct English translation of the word “harbola” (coined by Rabindranath Tagore when he met Rabin Bhattacharya).

Harbola is an art. Any random person can’t do it. It has to be rehearsed and practised. It has to be taken to the point of perfection. You see, art is a lifeform. Like us, it has a life too… a limited lifetime. The life of ventriloquism is almost over. It’s very old now. It’s in the ICU with ventilation. Everybody knows it’s going to die. But since it’s so close to me, I can’t let it die.

Narasingha shares his tragedy to Keshto about how his livelihood is fading away, just like “harbola” – an art that he so deeply possesses – and why he couldn’t part with it.

Indraadip Dasgupta, through his debut film, has touched on so many aspects of our society, psychology, philosophy and art in spite of having a very simple theme at its core. But it’s neither just the story of Narasingha, nor the various topics it brings up for discussion. It’s all about how he decides to tell it that weaves magic.

Despite the enormous impact of dialogues on the industry, cinema (though often called “talkies”) is intrinsically a visual medium. Visual storytelling is an art form, and when dialogue is stripped from it, it becomes more evident – quiet like in Kedara (the armchair). The film is a symphony of silence, echoing the mantra that every young filmmaker should be imbibed with: “Show, don’t tell.”