18th/19th c. Calcutta was the seat of the British Raj in India. Consequently, it witnessed a fusion of the East and the West, giving birth to the Bengali Renaissance – richly evident in the works of the great poet Rabindranath Tagore, and also the generation born to the educated middle-class around this time. Satyajit Ray was among them. Possessing innate cultural depth, he was a true product of the East and the West, imbuing him with traditional Bengali/Indian culture along with significant aspects of Western art and culture, one of which was cinema.

In his book “Our Films, Their Films” he has given an insight into the history of cinema – from the silent era to the 70s (when the book was written). While talking about filmmaking, he has repeatedly referred to and has shown glimpses of great directors like Vittorio De Sica, Jean Renoir, John Ford, Akiro Kurosawa and Charlie Chaplin – who were Ray’s absolute favourites and had a deep impact on his art. On his 101st birth anniversary, let’s have a look at some of these films that have had the biggest influences on one of the finest filmmakers ever – starting with the film that touched him the most and made him leave his job at an advertising company and create the humanist masterpiece that he is globally known for.

“What the trip did in fact was to set the seal of doom on my advertising career. Within three days of arriving in London I saw Bicycle Thieves. I knew immediately that if I ever made a Pather Panchali – and the idea had been at the back of my mind for some time – I would make it in the same way, using natural locations and unknown actors. All through my stay in London, the lessons of Bicycle Thieves and neo-realist cinema stayed with me. On the way back I drafted out my first treatment of Pather Panchali.”

Ray on his six-month trip to London, while working for an advertising agency. Our Films, Their Films.

Ray’s Apu Trilogy, especially Pather Panchali became the beacon of Indian cinema and made the world sit up and take notice of Indian films. It also gave rise to an Indian new wave of parallel cinema, to tell real human stories through films. All of this was because of how much this film gripped Ray’s imagination and confirmed his belief in this approach to filmmaking.

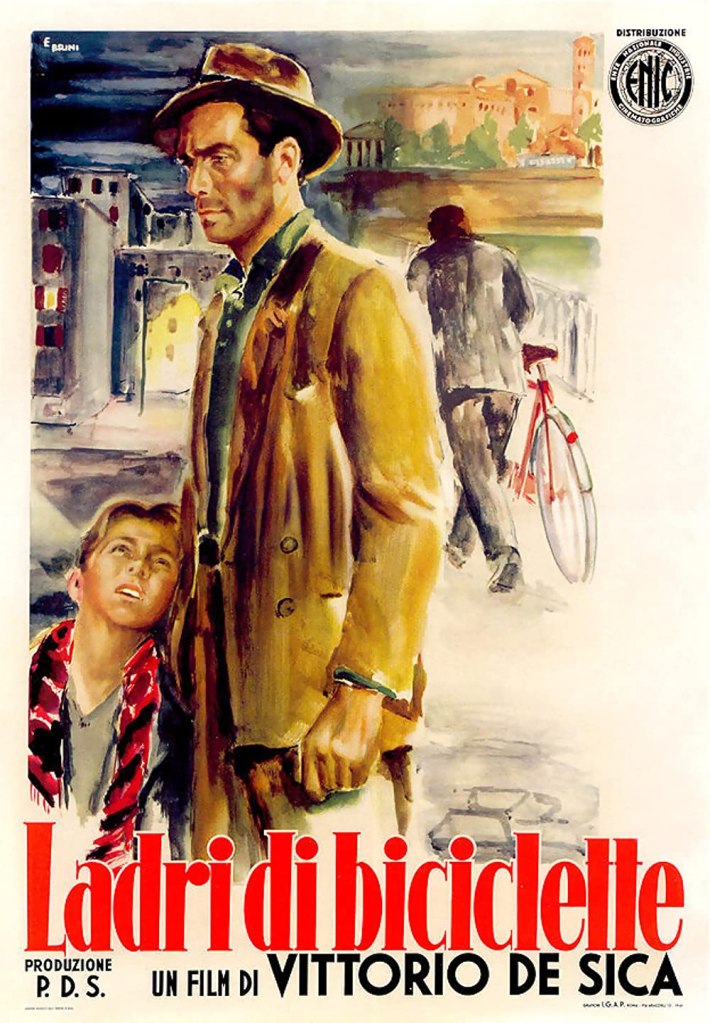

Hailed as one of the greatest films of all time, awarded an honorary Oscar in 1949, and revered as one of the foundation stones of Italian neorealism, Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves is a tender and simple tale of a man facing the perils of unemployment and poverty.

Based on a book by Luigi Bartolini, with a script by Cesare Zavattini – written exclusively with the camera in mind – this film is set in post-war Italy, just freed from the Fascist government, and works both like a political parable and a spiritual fable. It puts up a brutal mirror at the society and the conditions of the working class after World War II, but also ventures into the state of an individual soul – our protagonist Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani), whose bicycle (which his wife helps to get by pawning their bedsheets) is stolen on the first day of a new job that offered his desperate family hope of salvation. With his little boy in tow, he sets off to track down the thief and to find his bicycle, without which he would lose his job, and eventually his life.

Vittorio De Sica began as a theatre actor in the early 1920s and became an immensely popular film actor in the ’30s, before taking to directing in 1940. He a leading figure in the neorealist movement – a golden age in Italian filmmaking. This movement brought a revolution in the world of cinema, quite because of its sharp contrast to the American films at the time. These films were shot on location, usually with non-professional actors and the stories were set amongst the poor and the working class in post-WWII Italy. De Sica (along with Rossellini, Visconti) was at the helm of this movement with films such as I Bambini Ci Guardano (1944) and Shoeshine (1946) before making the masterpiece Bicycle Theives (1948).

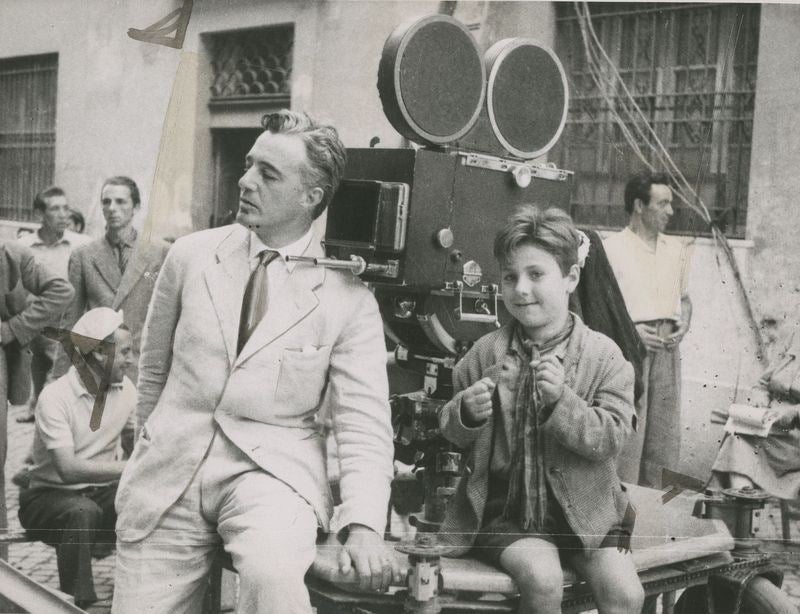

The fact that non-actors were used gives the film a strong element of authenticity. Their faces are so expressive, that they seem to be playing themselves. Lamberto Maggiorani had never been in a film before starring as Antonio. Even as desperation increases for his character, he brings steady masculinity to it. Enzo Staiola, the child who plays Antonio’s son Bruno – whom De Sica got from the streets after noticing his distinctive walk – is completely self-possessed and undaunted, regardless of the obstacles he and his father encounter as the day goes on. And yet, there’s also an obvious childlike honesty to him that is very engaging. Their bond as the father and son never seems fictional. Especially in the scene at the diner and the final act, both of them shine as seasoned actors in their prime, elevating beautiful Zavattini’s screenplay to another level.

There is no room for melodrama. De Sica’s characters have efficient and pragmatic conversations. At the start of the film, when Antonio goes home to tell his wife (Lianella Carell) he needs to buy a bicycle for his new job, she immediately strips their bed in order to sell their sheets without thinking twice.

The bicycle theft itself just happens like a random event that comes out of nowhere in the middle of a bustling city. There is no big build-up. And as Antonio goes on his quest to retrieve it, Bruno by his side, De Sica immerses us in the street life of Rome, filled with regular people – everyone fighting their own battle for survival – making up a sea of humanity.

There are simple pleasures to be found within this sad setting – dewy streaks of morning light through the alleys as the men make their way to work, an absurd comedic subplot at the church, or various moments of father-son bonding as Antonio and Bruno ride into town together with the wind in their hair or they enjoy a plate of mozzarella sandwich and wine after spending the day scouring the city for the stolen bicycle. De Sica offers these glimpses of hope along the way.

Vittorio De Sica uses this deceptively simple tale as an intimate and vivid way to explore the economic struggles of everyday people in post-war Italy. Even though the time and place of the setting are specific, the themes Bicycle Thieves conveys are universal and ever-relevant – the pressure to support one’s family, the drive to find financial security, the challenges of being a good parent in dire situations and the need to seek justice after being wronged. Without this film, Pather Panchali might not have been made and Ray’s belief in humanist cinema might not be confirmed. Decades later, we still see the influence of Bicycle Thieves in a variety of genres and languages, from Children of Heaven (1999) to The Florida Project (2019).

Bicycle Thieves, (and all the neo-realist, humanist films including Ray’s Pather Panchali) had only one intention: to tell a real, human story. This film, with a quality of a documentary, gave meaning to the common man. The characters are just ordinary people, and we watch their lives unfold before us. It teaches us about determining what we can and cannot change in this brutal reality of life and gaining the wisdom to know the difference.

If you haven’t watched this beautiful work of art, have a look at the trailer below, go watch it (it’s available on YouTube), and it will be evident how much De Sica’s neo-realist masterpiece inspired Ray to create his.